Biology Worthy of Life

An experiment in revivifying biology

A Physicist, a Philologist, and the Meaning of Life

Revised August 5, 2018. The revisions include an added subsection.

The celebrated physicist Richard Feynman, skeptical of religious and mythic creation stories that focus upon humans and the meaning of their lives, once explained his doubt with arresting simplicity: “The stage is too big for the drama”.1 The improbably large stage he had in mind was, of course, the boundless frontier explored by cosmologists, whose probing, high-tech sensors have mapped inter-galactic dimensions of space and time so far beyond our immediate experience that we humans can scarcely hope to comprehend them.

We have all heard many times about our nondescript place upon this vast stage. We are situated in an unremarkable galaxy among billions of others. Our solar system occupies a scarcely noticeable patch of real estate well out into this galaxy’s hinterlands. And, following the Copernican revolution, we earthlings lost even the circling attention of our neighboring sun and planets.

Still, we reigned unchallenged on our own planet, where we imagined ourselves the possessors of a special destiny, above all other creatures. But then, as a final insult, Darwin re-told our local creation story as a wearyingly long series of accidents, after which we found ourselves to be “trousered apes”.

Oh, the ignominy of it! Or, at least, that seems the usual point of the story. And, to be sure, it stings. The entire account can feel like a soul-crushing blow, rendering coarse or absurd all our higher aspirations, our ideals, our loves.

As a new creation myth, the story is compelling. Like any good myth, it pervades our culture. No one is surprised when a student of ancient Greek philosophy is given space in the New York Times to tell us why “The Universe Doesn’t Care About Your ‘Purpose’”. With no slightest flicker of troubling doubt, Joseph Carter assures us that “the universe certainly started with a bang, but it likely ends with a fizzle. What’s the purpose in that though? There isn’t one … In the grand scheme of things, you and I are enormously insignificant”.2

This pessimism may have been given its most quotable expression by French biochemist and Nobel prizewinner Jacques Monod in his book, Chance and Necessity:

Man must at last wake out of his millenary dream; and in doing so, wake to his total solitude, his fundamental isolation. Now he at last realizes that, like a gypsy, he lives on the boundary of an alien world. A world that is deaf to his music, just as indifferent to his hopes as it is to his suffering or his crimes.3

Monod’s mood of poetic high tragedy shifts toward prosaic resignation in the voice of another Nobel recipient, the physicist Steven Weinberg: “The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless”.4

Given this in some ways admirable spirit of humility, one might have expected the confessions of human insignificance to be accompanied by an acknowledgment of the severe and fundamental limits to current human understanding. Of course, this might have shadowed the odd and unusually bright self-confidence evident in many of these self-abnegators. Then there is the question why, in their self-confidence, they ignore the remarkable significance of the understanding we do have. And most puzzling of all — this will be the main burden of my discussion — is their failure to reckon with the historical record bearing on their claim that the world is alien, or at least indifferent, to human meaning, value, and purpose.

The sobering weight

of our ignorance

As children of the scientific revolution, we have securely vested our sense of knowing in quantitative precision and unambiguous, machine-like causation.5 Science becomes technology, where the aim is to construct instruments that respond exactly and predictably to carefully specified conditions. The cockpit of every jet airliner, the technical apparatus of a typical research laboratory, and the cell phones in the hands of nearly all of us proclaim how wonderfully well we have succeeded.

And surely our technological prowess does reflect a practical knowledge of the world. But the pleasure and wonder of it easily blinds us to the fact that we remain infants in fundamental understanding. How often do we remind ourselves that the nature of matter and energy is a mystery to us, or that, when we speak of “the physical”, it is difficult to indicate even roughly what we mean? When we get down to the submicroscopic specifics, we find nothing there, no thing of any recognizable sort. We identify reliable mathematical relations suggesting particular structure, but we do not know: the structure of what?

Joseph Carter, in the article cited above, finds it natural to say, without blinking an eye, “As a materialist, I think …” — as if “material” and “matter” were perfectly routine concepts. Yet I doubt whether any philosopher of science today would be so rash as to venture a confident definition of “matter”. Certainly our technological know-how does little to lend it content.

Much the same can be said of the terms often considered basic to science, such as energy, space, force, and time. Feynman himself remarked in his famous lectures that “we have no knowledge of what energy is”.6 Anyone who senses the disquieting shadow of the unknown enveloping our science will hardly pronounce upon the true nature of the “material” world. To do so might only suggest a tendency toward insecure bluster and a habit of uncritical thinking.

Things get no better when we turn to the problem of consciousness, which we might well think of as fundamental to all other perplexities we confront in thought and experience. The late Jerry Fodor, an eminent philosopher of mind who spent much of his life working on this problem, was convinced that “Nobody has the slightest idea how anything material could be conscious. Nobody even knows what it would be like to have the slightest idea about how anything material could be conscious.”7

Then there is British philosopher Colin McGinn, who depicts a fictionalized, super-intelligent alien marveling at the glibness of a human cognitive science that claims to explain the emergence of consciousness from matter: “You might as well assert, without further explanation, that space emerges from time, or numbers from biscuits, or ethics from rhubarb”.8 And David Chalmers, one of the most heavily cited cognitive scientists of our day, has admitted that “it wouldn’t surprise me in the least if in 100 years, neuroscience is incredibly sophisticated, if we have a complete map of the brain — and yet some people are still saying, ‘Yes, but how does any of that give you consciousness?’ while others are saying ‘No, no, no — that just is the consciousness!’”9 The entire field of consciousness studies remains today in ferment, with no evident prospects for breakthrough discoveries.

We should keep in mind just how dramatic are the implications of our ignorance. The confessions we have just heard amount to saying that our science altogether lacks support at the deepest level. I mean the level at which we try to understand what, if anything, our scientific thoughts tell us about reality — or even how we can distinguish between “the world” and the conscious processes through which alone the world exists for us.

The only science we have is a

science of human experience

But perhaps more remarkable than the darkness of the unknown is the refreshing light of our apparent understanding. Albert Einstein once claimed that “the eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility”, which he called a “miracle”.10 This comprehensibility, presenting us with a puzzle logically prior to questions about the particular nature of matter, energy, space, and all the rest, may be far the most fundamental fact of our own, and the world’s, existence.

Einstein meant, of course, comprehensible for us. It is obvious enough that we have no science and no knowledge of the world except by means of our own experience. If we could not reliably start with our experience, we could not know anything. The only world we can investigate is the one that takes form within our understanding minds.

In slightly different words, the content of our science is always mediated by human consciousness. We can conceive the world only by conceiving it. Reality, whatever else we may say about it, must share in the character of thought; otherwise we would not be able to embrace it with our thinking. We can have no idea of things that, in their own nature, are entirely non-ideational. “A reality completely independent of the mind which conceives it, sees or feels it,” wrote the French mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré, “is an impossibility.”11 This is a remarkable truth for any materialist to behold: the natural world lights up as a reality within our human minds!

I don’t suppose there could be a more startling disconnect than when a knowledge seeker aims to articulate a conceptual understanding of a world he considers inherently meaningless. A conceptual articulation, after all, is nothing other than the working out of a pattern of interwoven meanings. A truly meaningless world would offer no purchase for this effort. We cannot understand what, in and of itself, makes no sense.

If we believe that an empirical (experience-based) science — a science grounded in the conceptual ordering of sensible appearances — really does give us genuine knowledge of the world, then a reasonable conclusion is that this world is, by nature, a realm of conceptually ordered appearances possessing the qualities of sense. It asserts its existence and character in the terms of conscious, thought- and sense-derived experience.

Today such a view is bound to seem strange. We are shielded from it by the historically eccentric conviction of the past few hundred years that our thought and experience, so thoroughly bound up with qualities, are merely subjective. Qualities such as color, taste, smell, and feel are “in our heads”, not “out there in the world”. We have done our best to rid science of these supposed phantoms of subjectivity by turning to the rewards of quantitative analysis.

But, as anyone can verify with a moment’s reflection, subtracting all the qualities from our picture of the material world erases the entire picture. There is no content — nothing but a blank — without the qualities of experience. Mathematics alone, without the qualities of actual things, is not about anything material. And we should not forget that mathematics itself is a content of thought. This thought is not merely “in our heads”; it is also in the world, which is why we so readily discover our mathematical ideas in physical phenomena. Our inner experience and the material world are not mutually alienated.

Having done their best to deprive themselves of the qualities that alone can give them a sensible world, and therefore being left with an applied mathematics shaped only by the demands of technological workability, most working physicists have long considered it disreputable even to discuss the reality their science refers to. By the middle of the last century — so say two accomplished physicists — “any nontenured faculty member in a physics department would endanger his or her career by showing interest in the implications of quantum theory”.12 Nor has the more recently renewed, if still minority, interest in the meaning of physical theory yielded anything like consensus or resolution of the fundamental perplexities.

And so the question, “What sort of world do we live in?” came to be enveloped in darkness precisely at the point where our science was thought to be most fundamental! We have a physics of light and color framed as far as possible in language suitable for those who cannot see, and a science of acoustics that might just as well have been formulated by those who cannot hear.

The dismissal of qualities from science — which is to say, the dismissal of the world of experience — has meant that physicists, when they venture at all beyond their equations and well-designed instruments, lose themselves in a Wild West of speculation, illustrated by the “many worlds” theories so prominently heralded today. This is high-flying conjecture that puts to shame those medieval doctors whose soaring intellectual acrobatics were precisely what the pioneers of the Scientific Revolution so badly wanted to bring down to earth, where ideas could be tested within human experience.

The instincts of those pioneers were sound. A science of human experience is the only science of reality we can have. And what seemed to startle Einstein into an invocation of the “miraculous” was the fact that we can have it.

The world’s speech

resounds in us

According to the evolutionary story that most of us have forcibly absorbed from a young age, humankind somehow raised itself above the beastly, mindless, material substrate of its origin so as to achieve, step by step, the mystifying wonders of language and poetry, music and art, politics and science, and all the other sublimations contributing to high culture. The sea of meaning within which we now swim — without which we would have nothing we could recognize as human life — somehow bubbled up from somewhere, if only as an illusion of the human mind, and cast a kind of spell over the bedrock meaninglessness of brute matter.

“Somehow”, I say, since the meaning at issue, and the question how it could have emerged from an eternal silence of Unmeaning is so great an enigma for conventional thinking that it has received no fundamental elucidation. Nor is it evident that we need to seek an origin of meaning. Perhaps what we will actually discover is a larger, meaning-soaked surround, progressively coming to a focus in human minds.

The first thing to notice is that, looking further and further back in the direction of our “material” roots, we find something like the opposite of the conventional picture. As the nineteenth-century English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley observed, “In the infancy of society every author is necessarily a poet, because language itself is poetry”. And it was the whole business of this poetry to apprehend the “true”, the “beautiful”, and the “good”.13

We do not, that is, discover ancient literature to be impoverished relative to a modern literature expressing the multi-layered richness of meaning arising from millennia of literate cultural accretion. It is more like the reverse of this: we still debate today whether, for example, the Homeric epics — composed orally before the development of writing in ancient Greece — have ever been surpassed for psychological depth, dramatic power, and human interest.

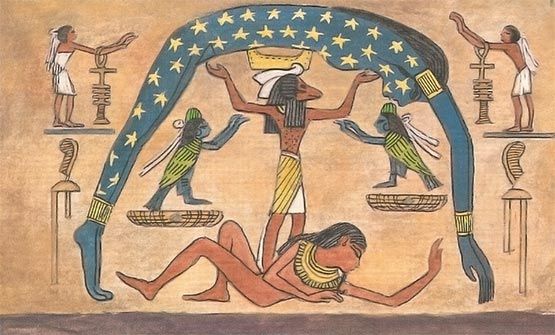

Likewise, the earliest “histories” did not describe cavemen going on adventures with clubs. The accounts were more like spiritual and cosmic histories. Humans — their gaze riveted by fascinating goings-on in what we today might denigrate as “supernatural” realms, but which they experienced simply as nature — did not narrate their own histories. Rather, as is still echoed in Hesiod’s Theogony long after the primary age of myth, they told stories of the genesis of gods and nature spirits. Only with time did history become more human-centered and prosaic.

And, again: “The farther back language as a whole is traced, the more poetical and animated do its sources appear, until it seems at last to dissolve into a kind of mist of myth. The beneficence or malignance — what may be called the soul-qualities — of natural phenomena, such as clouds or plants or animals, make a more vivid impression at this time than their outer shapes and appearances. Words themselves are felt to be alive and to exert a magical influence”.14

Consciousness, too, evolves. That last remark was from the British philologist and semantic historian, Owen Barfield. His death in 1997 deprived us of a rare authority on language and meaning who actually looked at the changing nature of human consciousness so far as the historical record allows. The fundamental premise underlying his work was that how we look at the human past is decisive, for there is a crucial distinction between the history of ideas and the evolution of consciousness. About the former he wrote:

A history of thought, as such, amounts to a dialectical or syllogistic process, the thoughts of one age arising discursively out of, challenging, and modifying the thoughts and discoveries of the previous one.

On the other hand, we must employ a different manner of investigation if we would come to terms with the evolution of consciousness. Our method must

attempt to penetrate into the very texture and activity of thought, rather than to collate conclusions. It is concerned, semantically, with the way in which words are used rather than with the product of discourse. Expressed in terms of logic, its business is more with the proposition than with the syllogism and more with the term than with the proposition.15

It was to this evolutionary study that Barfield continually returned as he illustrated, in a series of works spanning much of the twentieth century, how the meanings of words “are flashing, iridescent shapes like flames — ever-flickering vestiges of the slowly evolving consciousness beneath them.”16 He tried to show that the processes of evolution, while not determining the particular ideas of a given era, do circumscribe the kinds of things one can conceive and mean. As an example, the historian Herbert Butterfield, whom Barfield cites, describes how the Aristotelian worldview gave way during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries:

Through changes in the habitual use of words, certain things in the natural philosophy of Aristotle had now acquired a coarsened meaning or were actually misunderstood. It may not be easy to say why such a thing should have happened, but men unconsciously betray the fact that a certain Aristotelian thesis simply has no meaning for them any longer — they just cannot think of the stars and heavenly bodies as things without weight even when the book tells them to do so. Francis Bacon seems unable to say anything except that it is obvious that these heavenly bodies have weight, like any other kind of matter which we meet in our experience.

Butterfield adds that there was, during this period, “an intellectual transition which involves somewhere or other a change in men’s feeling for matter.17

Barfield was convinced that, in failing to become aware of the evolution of consciousness underlying the history of ideas — an evolution that includes the changing cognitive relation between the perceiver and what he perceives — we lose the ability to understand the life of earlier eras, and therefore we become entrapped in modernity. It was from this entrapment that he was eager to deliver his readers. “We are well supplied with interesting writers”, the novelist Saul Bellow wrote, “but Owen Barfield is not content to be merely interesting. His ambition is to set us free. Free from what? From the prison we have made for ourselves by our ways of knowing, our limited and false habits of thought, our ‘common sense’.”18

We have learned, especially since Darwin, that knowledge of the past illuminates the biological present — that, as the mantra of contemporary evolutionary theorists would have it, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”.19 The mantra could serve as Barfield’s theme as well, but with this difference: he did not forget to include consciousness in that which evolves. The omission, after all, looks on its face to be disastrous. If we had no hope of fully understanding the biology of organisms before the idea of evolution dawned upon us, how much more must we remain in darkness while ignoring the evolution of the cognitive instruments through which alone we can grasp that idea — that is, while ignoring the evolution of the instruments of our understanding itself.

The following sections may afford a few glimpses of what this means.

A primordial unity of inner and outer meaning.

The “enchanted” landscape of mythic consciousness, as Barfield sketches it for example in Poetic Diction, could not have been one of conscious invention, unrestrained metaphor, or causal speculation. The earliest ancestors of which we can form any picture at all could only observe nature as it was given to them. Their meanings did not arise from anything like modern reflection or theorizing, but were encountered directly.

This truth has been disguised from us by what Barfield referred to as “logomorphism” — the projection of modern thought processes onto “that luckless dustbin” of the primitive mind. “The remoter ancestors of Homer, we are given to understand, observing that it was darker in winter than in summer, immediately decided that there must be some ‘cause’ for this ‘phenomenon’, and had no difficulty in tossing off the ‘theory’ of, say, Demeter and Persephone, to account for it”.20

But we see no evidence that the mythic mind had any concern with such explanations, if only because the conditions for them did not yet exist. For one thing, explanation requires distinct ideas — something to be explained, on one hand, and an explanation for it, on the other. But the outer and inner aspects of the unity that our ancestors experienced — which theorists today want to dualize into material fact and fanciful, immaterial explanation — were not separable in that sort of way. The mythically enchanted landscape was an unanalyzed interfusion of outer and inner, of sense perceptions and soul content.

For example, the story of the Greek sun-god “Helios” could hardly have originated as an animistic effort to account for a material sun, given that neither the history of language nor what we know of mythic consciousness affords any evidence that a purely material sun had yet been conceived. The sun’s glory, its light and warmth, were directly and non-reflectively experienced as ensouled realities.

We still find remnants of such indivisible meaning in later eras, as when we read in the New Testament,

Truly, truly I say to you, unless one is born of water and the spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God … The wind blows where it wishes and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from and where it is going; so is everyone who is born of the spirit. (John 3:5-8)

Translators into English (here in the New American Standard Bible) have been forced to use two different words, “spirit” and “wind” (in other texts “breath” is required) where the original Greek has a single word, pneuma. “We must, therefore, imagine a time”, Barfield noted, “when [Latin] ‘spiritus’ or [Greek] ‘pneuma’, or older words from which these had descended, meant neither breath, nor wind, nor spirit, nor yet all three of these things, but when they simply had their own old peculiar meaning, which has since, in the course of the evolution of consciousness, crystallized into the three meanings specified”.21

“Nor yet all three of these things” — not the addition of one distinct meaning to another, but a single unity of wind, breath, and spirit. Today’s largely disconnected meanings simply weren’t there yet in human experience. It is hard for us to appreciate this at a time when our language forces a dichotomous choice between the terms of outward, sensible reference and those drawn from our interior life. To take one further example, this one from Barfield’s History in English Words:

As far back as we can trace them, the Sanskrit word “dyaus”, the Greek “zeus” (accusative “dia”), and the Teutonic “tiu” were all used in contexts where we should use the word sky; but the same words were also used to mean God, the Supreme Being, the Father of all the other gods … If we are to judge from language, we must assume that when our earliest ancestors looked up to the blue vault they felt that they saw not merely a place, whether heavenly or earthly, but the bodily vesture, as it were, of a living Being.22

Summing up the historical picture, the American transcendentalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson, wrote in his 1836 book, Nature, “As we go back in history, language becomes more picturesque, until its infancy, when it is all poetry; or all spiritual facts are represented by natural symbols”. And again: “It is not words only that are emblematic; it is things which are emblematic.”23

So the direction of the evolution of language and meaning is, so far as we can discern from the historical record, the opposite of an “ascent from brute materiality”. Before humans could speak in their own individuated voices, or could even conceive of devising theories or telling their own stories in a modern biographical sense, the natural world spoke to and through them. The rhythm and meter we find, for example, in the epic Homerian hexameters with their “thundering epithets” were, Barfield wrote, relics of a time “when men were conscious, not merely in their heads, but in the beating of their hearts and the pulsing of their blood — when thinking was not merely of Nature, but was Nature herself.”24

Nature’s ‘speech’ gave us our meanings. Historically, then, nature presented us with exteriors whose inner significances were, so to speak, written on their faces. Phenomena constituted a living language, rather as, still for us today, the sense-perceptible human face can scarcely be distinguished from its expressive eloquence — from the meaning it communicates. Similarly, it was from the evocative countenances of nature that our forebears discovered, in a living unity, the profound potentials of meaning that eventually yielded our current, analytically refined language.

The history of language gives us ample evidence pointing back to the kind of inner/outer unity evidenced in the Greek pneuma. We see this in two broad classes of words:

• Some words — those now bearing immaterial meaning in the form of high abstraction, or else referring to our interior life — were once inseparable from sensible experience. “Right” meant “straight”; “wrong” meant “twisted”. To “conceive” something was to “grasp” it, as with the hand. Only with time did the abstract or inner meanings become detached from sense perception.25

• The other group of words, now referring to material, sense-perceptible phenomena, once also connoted sentience or inwardness. We have already seen how words for “sky” also meant “divine being”. “Matter” itself likely traces back to Latin mater, “mother”. And “physical” derives from Greek phyein, “grow”. So the Greek ta physika — “natural things” or “things of external nature” — was rooted in living activity.

In this way much of our language testifies to the primeval experience of nature as a material/immaterial, outer/inner unity. But none of this is to say we should look to etymology for current meanings. Will anyone claim today that when we say someone is “wrong”, we mean he is bent like a stick, or that to “conceive” something is to grasp it physically? Nevertheless, the history of meaning raises its own questions.

How could the meanings of our ancestors have possessed their primordial, immaterial aspects if the sense-based images (a bent stick, the hand’s grasp) did not, out of their own nature, lend themselves to the expression of those aspects?26 If the relation between sensible image and immaterial meaning were arbitrarily invented by early speakers and were not inherent in the phenomena themselves — if things were not, as we heard from Emerson, emblematic — how would anyone have understood the speakers’ “invented”, immaterial meanings?

In today’s terms: we may not mean “bent like a stick” when we say “wrong”, but who can deny that the material image of a bent object carries within it a potential for such inner meaning — the kind of meaning we find present today in the English “bent”, which can mean “strongly inclined, resolved, or determined”? The original emblematic, or symbolic, meanings of things were not inventions. In the mythic consciousness, according to Barfield, thinking was “at the same time perceiving — a picture-thinking, a figurative, or imaginative, consciousness, which we can only grasp today by true analogy with the imagery of our poets, and, to some extent, with our own dreams.”27

This picture-thinking was given by nature. The thinking element — the expressive content — was not added by a reflective or theorizing perceiver, but was already experienced in perception. Things meant something on their face. Our ancestors were, in a sense, participant-observers entranced by an ensouled drama staged within their own consciousness by the phenomena.28

What the historical record shows is that those ancestors recognized, in whatever was expressed through natural phenomena, a speaking agency akin to themselves. “Whether it is called ‘mana’”, wrote Barfield, “or by the names of many gods and demons, or God the Father, or the spirit world, it is of the same nature as the perceiving self, inasmuch as it is not mechanical or accidental, but psychic and voluntary.”29

We can make of all this what we will today, when our evolutionary trajectory, as Barfield traces it (and as I cannot here), has brought us to a vastly different place. But whatever case we choose to argue, we will necessarily invoke meanings that are available to us only because the world first put those meanings on display, enabling them to light up in nascent human minds.

At the same time, we will need to acknowledge that, so far as the historical record testifies, our evolutionary trajectory has not accorded with the usual assumptions. There is no evidence that we slowly ascended from a crude life of material unmeaning to a humanly contrived realm of meaning, value, culture, and spirituality. Our life today, with its materialistic convictions about the meaninglessness of nature, has required a long descent from the living, ensouled landscape upon which our ancestors were nurtured.

Our Cartesian heritage has taught us well to insist upon a radical separation of the inner and outer dimensions of our experience, which once formed so compelling a unity. And then, under the further influence of materialist thought, we have learned to regard the inner dimension as “merely subjective” or somehow less than fully real. This suggests that, instead of projecting our current mental processes upon the “ignorant” ancients, we might want to consider how a Cartesian and materialist heritage may have concealed an ancient wisdom, finally concreting in our own deepest, most unyielding, and largely unconscious habits of thought and experience.

Through such reflection, perhaps we would gain the freedom within ourselves at least to inquire in all seriousness whether we today are the ones who lack ready access to much of the world’s reality.

Why make our lives

a drama too small

for the stage?

We have seen that a great unknown presses in upon us from all sides. Despite our impressive technological successes, the fundamental terms of our science remain seemingly impenetrable mysteries. What one physicist wrote in 1985 is no less true today: “As yet no physicist can tell you what sort of world we happen to live in”.30 Humbling as it may seem in an era so arrogantly dismissive of the past, our current physical science gives us no basis for belittling the ancient human experience of living in something rather more like a universe of beings than a universe of things.

But we have also seen that an intelligible world is more intimately near to us than most of us have dared to hope. If we understand the world at all — and we are all convinced we do — it can only be because it consists, by nature, of qualitative appearances (“phenomena”) available to experience. It presents itself on the stage of our inner being.

And, finally, by looking at the history of language we have seen that the expressive face of the world appeared to our ancestors as a kind of speech, and it was from this presentation that our own powers of speech derived. Like language, every natural phenomenon was an exterior through which there shone interior significances. The essential elements of nature were not mute, expressionless things, but resonant images symbolizing meanings.

We return, then, to Feynman’s statement. When he said the stage is too big for the drama, he must already have concluded that the drama is sadly insignificant. Otherwise, what could have suggested that the stage is too big? And, more to the point of all the foregoing, he was assuming a vast cosmic expanse indifferently related to the human story. But this assumption is the whole point at issue.

It is not at all clear how a universe of appearing things — things declaring themselves to us and bearing the sources of our language and thought within them — could possibly be alien to our own story. Not only have we drawn our interior life from the world’s meanings, both sublime and awful, but we live in a world whose very nature is to be encompassed within our consciousness — to live within us. Far from finding ourselves strangers in an alien universe, we embrace with our imagination and understanding the most distant galaxies, bearing witness to the significances of their light.

The universe’s appeal to our inner being runs deeper than intellect alone. For one thing — and what mystery could be more profound? — the world yields itself gracefully to the choreography of our purposeful action. We, by means of our inwardness, are able to rearrange nature’s physical furniture — such is the intimate access the world so naturally grants to our thought and will. And, beyond this, the entire cosmos is a boundless source of inspiration and encouragement. J. R. R. Tolkien reminds us of this when, in The Lord of the Rings, Frodo catches a momentary glimpse of a single star on high, penetrating the gloom of Mordor:

The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.

Perhaps the truth is nearly the reverse of Feynman’s saying. What is to prevent us from thinking that our receptive, respectful, and attentive consciousness is the stage, or one stage, upon which the material universe is itself realized — upon which it comes to its essential appearance? The question then is whether we have made this stage too small to accommodate nature’s eloquence — the qualitative and full-throated eloquence that, for all we know, desperately needs our own consciousness, conscience, and voice for its own most profound expression.

We are, of course, free to shrink the stage of our consciousness until it can present us only with a pitiful, mechanistic reduction of the natural world’s performance. But we can reasonably hope that the cosmos that so patiently brought us forth — a cosmos whose expressive material is woven through our own being — will tolerate a few centuries’ foolishness during which, like adolescents leaving home to establish their independence, we struggle against the “tyranny” of our upbringing. It is, in its way, a noble and necessary struggle. And if it has yielded, among other things, Richard Feynman’s devotion to disciplined truth within the sphere of his own inquiry, this is something to be cherished.

Yet, as we know so well, merely efficient truth is capable of great destruction. A lot may depend on our gaining trust in the meaning and dignity of our own story. And this will prove impossible, I suspect, except insofar as we also renew our trust in nature’s meaningful appearances — in the beautiful, compelling, sobering, terrifying, and inspiring phenomena it has so freely entrusted to us as the basis, not only for any genuine science, but also for the plenitude of our inner lives.

Notes

1. Quoted in Gleick 1992, p. 372.

2. Carter 2017.

3. Monod 1971, p. 160.

4. Weinberg 1993, p. 154.

5. See Talbott 2004.

6. Feynman, Leighton, and Sands 1963, p. 4-2.

7. Fodor 1992.

8. McGinn 2004, p. 145.

9. Quoted in Burkeman 2015.

11. Poincaré 1913, Introduction.

12. Rosenblum and Kuttner 2006, p. 13.

14. Barfield 1967, pp. 87-8.

15. Barfield 1965, pp. 67, 90.

16. Barfield 1973, p. 75.

17. Butterfield 1957, pp. 130-1.

18. From Bellow’s book-jacket testimonial for Barfield’s History, Guilt and Habit (Barfield 1979).

19. This was the title of an article by the twentieth-century evolutionary theorist, Theodosius Dobzhansky.

20. Barfield 1973, pp. 74, 90.

21. Barfield 1973, pp. 79-81.

22. Barfield 1967, pp. 88-9.

24. Barfield 1973, pp. 146-7.

25. Barfield 1973, p. 134.

26. For a treatment of this and related questions, see Barfield’s remarkable essay, “The Meaning of ‘Literal’” in The Rediscovery of Meaning and Other Essays, pp. 32-43. Perhaps equally valuable is his essay on “The Nature of Meaning”.

27. Barfield 1973, pp. 206-7.

28. Barfield, I think, would say we must also come to terms with the reverse truth: the phenomena are themselves an ensouled drama staged in the “outer” world by human consciousness. That is, consciousness and the phenomena are correlative. But this radical notion would take us far beyond the current exposition.

29. Barfield 1965, p. 42.

30. Herbert 1985, p. 146.

Sources:

Barfield, Owen (1965). Saving the Appearances. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World. Originally published in 1957.

Barfield, Owen (1967). History in English Words. Grand Rapids MI: William B. Eerdmans. Originally published in 1926.

Barfield, Owen (1971). What Coleridge Thought. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Barfield, Owen (1973). Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press. Originally published in 1928.

Barfield, Owen (1977). The Rediscovery of Meaning, and Other Essays. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Barfield, Owen (1979). History, Guilt, and Habit. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Barfield, Owen (1981). “The Nature of Meaning”, Seven vol. 2, pp. 32-43.

Burkeman, Oliver (2015). “Why Can’t the World’s Greatest Minds Solve the Mystery of Consciousness?”, The Guardian (Jan. 21). https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jan/21/-sp-why-cant-worlds-greatest-minds-solve-mystery-consciousness

Butterfield, Herbert (1957). The Origins of Modern Science 1300-1800, revised edition. New York: Free Press.

Carter, Joseph P. (2017). “The Universe Doesn’t Care About Your ‘Purpose’”, New York Times (July 31). https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/31/opinion/the-universe-doesnt-care-about-your-purpose.html

Dobzhansky, Theodosius (1973). “Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution”, The American Biology Teacher vol. 35, no. 1 (Mar.), pp. 125-9. doi:10.2307/4444260

Einstein, Albert (1936). “Physik und Realität”, Franklin Institute Journal (March). For the English translation of the quote, see https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/q-oro-ed4-00003988 "https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/q- oro-ed4-00003988" "."

Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1836). Nature. Boston: James Munroe and Company. Available at https://archive.org/details/naturemunroe00emerrich.

Feynman, Richard, Robert B. Leighton and Matthew Sands (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, three volumes. Reading MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fodor, Jerry (1992). “The Big Idea: Can There Be a Science of Mind?”, Times Literary Supplement (July 3), p. 5-7.

Gleick, James (1992). Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman. New York: Random House.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von (1995). Scientific Studies, edited by Douglas Miller. Vol. 12 in Goethe: Collected Works. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Herbert, Nick (1985). Quantum Reality: Beyond the New Physics. New York: Doubleday.

McGinn, Colin (2004). Consciousness and Its Objects. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Monod, Jacques (1971). Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology, translated by Austryn Wainhouse. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. First published in French in 1970.

Poincaré, Henri (1913). The Value of Science, translated by George Bruce Halsted. Available at https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/p/poincare/henri/value-of-science/

Rosenblum, Bruce and Fred Kuttner (2006). Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe (1840). “A Defence of Poetry”, in Essays, Letters from Abroad, Translations and Fragments, by Percy Bysshe Shelley, edited by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. London : Edward Moxon. “A Defence of Poetry” was originally written in 1821 and published posthumously. Text is available at https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5428.

Steiner, Rudolf (1995). Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path, translated by Michael Lipson, foreword by Gertrude Reif Hughes. Hudson NY: Anthroposophic Press. Originally published in 1894 and revised in 1918.

Talbott, Stephen L. (2004). “The Reduction Complex”. http://BiologyWorthyofLife.org/mqual/ch04.htm

Weinberg, Steven (1993). The First Three Minutes, second edition. New York: Basic Books.

This document: https://bwo.life/org/comm/ar/2018/meaning_33.htm

Steve Talbott :: A Physicist, a Philologist, and the Meaning of Life