Teleology and Evolution

Every organism is continually dying in order to live. Breaking-down activities are prerequisites for building up. Complex molecules are synthesized, only to be degraded later, with their constituents recycled or excreted. In multicellular organisms such as vertebrates, many cells must die so that others may divide, proliferate, and differentiate. Many cancers reflect a failure to counterbalance proliferation with properly directed tearing-down processes.

You and I have distinct fingers and toes thanks to massive cell death during development. The early fetus’ paddle-like hands give way to the more mature form as cells die and the spaces between our digits are “hollowed out.” In general, our various organs are sculpted through cell death as well as cell growth and proliferation. During development the body produces far more neurons than the adult will possess, and an estimated ninety-five percent of the cell population of the immature thymus gland dies off by the time the mature gland is formed.1 Even in our adult bodies, a million or so cells die each second.2

Despite all this life and death, I doubt anyone would be tempted to describe an animal’s cells as figuratively “red in tooth and claw.” Nor do I think anyone would appeal to “survival of the fittest” or natural selection as a fundamental principle governing what goes on during healthy development. The life and death of cells appear to be governed, rather, by the form of the whole in whose development the cells are participating.

But this has been a truth hard for biologists to assimilate, since it has no explanation in the usual causal sense. One way to register the problem is to ask yourself what you would think if I suggested that members of an evolving species thrive or die off in a manner governed by the evolutionary outcome toward which they are headed — that the pattern of thriving and dying off becomes what it is because of that outcome. It is not a thought any evolutionist is likely to tolerate.

But perhaps the occasional intrepid researcher will be moved to inquire: “Why not?” After all, we can also ask about the cells populating our bodies: do they thrive or die off in a manner governed, in some sense, by the forthcoming adult form? And here the answer appears to be a self-evident “yes.”

Perhaps, when we can allow ourselves to reflect on what we see so clearly in individual development, we will find ourselves asking the “impossible” question about evolutionary trajectories: Does natural selection really drive evolution, or is it rather that the evolving form of a species or population drives what we think of as natural selection? Are some members of an evolving species — just as with the cells of an embryo’s hands — bearers of the future, while other members, no longer able to contribute to the developing form of the species, die out?

What makes this idea seem outrageous is the requirement that inheritances, matings, interactions with predators, and various other factors in a population should somehow be coordinated and constrained along a path of directed change. Unthinkable? But the problem remains: Why — when we see a no less dramatic, life-and-death, future-oriented coordination and constraint occurring within the populations of cells in your and my developing bodies — do we not regard our own development as equally unthinkable?

Or is it that we have simply learned to take for granted the coordination of cell births and deaths in the developing animal, since our extensive familiarity with animal development doesn’t seem to leave us much choice in the matter? But apparently we do have a choice about whether to reckon in any profound way with the implications of this coordination for our thinking about biology in general, and our choice seems to be: “Let’s just ignore it.” And perhaps we are most assiduous in our ignoring when our thoughts turn to evolution.

So the question I am raising is this: once we accept the all-too-evident fact of an immanent coordinating agency at play in a population of cells pursuing a developmental trajectory, do we not have good reason to inquire whether an immanent coordinating agency is also at play in any population of organisms that is in fact pursuing an evolutionary trajectory?

Our approach to this question will undoubtedly be influenced by the degree to which we have taken seriously a general truth stressed throughout the first half of this book: agency and intention, wisdom and meaning, are given expression in all biological activity in a way that belies our expectations for collected bits of inanimate matter.

It will be part of my contention in forthcoming chapters that a coordinating power at work in evolving populations is as obviously apparent as the analogous power at work in developing organisms. It’s not a conclusion based on radical new evidence, but rather one that depends only on a willingness to look at evolution with eyes that see, just as we do when observing a developing individual.

We will do our best to look in this way. But first we need to deal with some of the prejudices blocking our way forward. That’s what this chapter is about.

Are there obvious reasons to reject

agency and teleology in evolution?

Every living activity we actually observe is purposive, or “teleological,” or, as I have at times called it, “telos-realizing”. It always has a contextual (holistic) dimension, and it always represents a further addition to a life story. We find ourselves watching, not necessarily a conscious planning (which is natural to humans), but rather the self-expression, or self-realization, of living beings. Physical events and causes are coordinated in the interests of a more or less centered agency that we recognize in cell, organism, colony, population, and species.

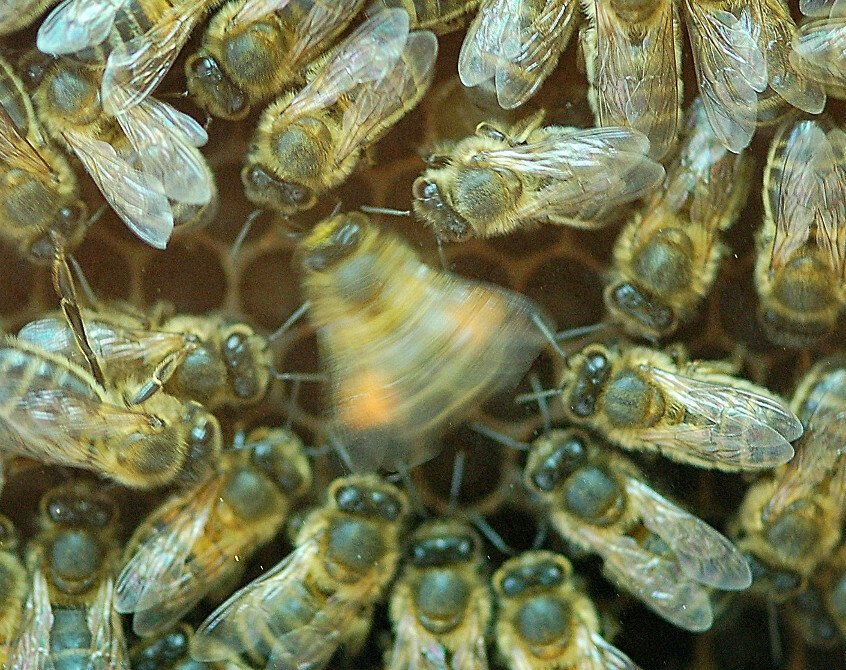

Figure 18.1. A waggle-dancing bee (blurred image in center). The waggle dance is one of the ways honey bees communicate in a colony — in this case by providing information about the direction, distance, and richness of a food source.3

This coordination, these interests, this agency — they are already assumed, consciously or otherwise, by all biologists in the case of the individual organism’s development and behavior. They are assumed, that is (as I have frequently been pointing out), insofar as one is doing biology, and not merely physics and chemistry. See Figure 18.1 for a well-known and meaningful performance in nature that would hardly raise an eyebrow among biologists.

I tried to suggest in the opening section of this chapter that the agency and purposiveness so clearly manifest in the development of individual organisms is something we might also want to consider in relation to evolution. But, to most biologists, this is bound to seem a rather wild conjecture, and an impossible one at that. Let’s listen to a few of the concerns that can so easily disturb our thinking about the role of agency — or, indeed, any sort of wisdom or intention (or, more broadly, interiority) — in evolution.

“How can you jump so casually from the hypothesized agency of a single, developing individual to that of vast, evolving populations?”

When we speak, not about physical processes as such, but rather about an underlying biological agency, intention, and purposiveness, then any radical distinction between an individual animal as a collection of molecules, cells, and tissues, on one hand, and entire populations as collections of animals, on the other, disappears. In neither case are we talking about the causal effect of discrete material things upon each other. Rather, we’re trying to apprehend a governing unity — a principle of form, or what has been called a “formal cause” — in which those things are caught up.

The whole business of telos-directed biological activity as we observe it throughout all biology is to bring radically diverse physical processes — for example, those in the brain, heart, liver, intestines, and skin of a developing mammal — into a harmonious context, making a unified whole of them. As we have seen in Chapter 6 (“Context: Dare We Call It Holism?”), the unity of idea and meaning that makes for a context is not graspable in purely physical terms. Ideas and meanings are not physical entities, nor is their unity delimited by the boundaries we so easily imagine between physical things. Further, once we acknowledge the reality of purposive coordination and harmonization in one organic context involving many interrelated physical things, we have no reason not to look for it in other organic contexts involving different collections of physical things.

Of course, if one insists that all aspects of our understanding of life must be couched solely in terms of lawful physical interactions, then it will be impossible to accept anything I am saying here. But this insistence is exactly what I am now questioning. The biologist may want to quarrel with the present argument, but the quarrel cannot be furthered by endlessly repeating the very idea that is being disputed. It adds nothing to the discussion when one says, “The meanings you claim to be evident in all biological activity shouldn’t be mentioned because we’re bound by the rule that only physical interactions can be considered.” That rule is the entire issue at hand. Those who want to argue that the meanings aren’t really there should do so, or otherwise hold their peace. (Their argument, if they have one, is with the entire first half of this book.)

It may be that we no more understand the nature and origin of the observed powers of meaningful coordination in living organisms than we do the nature and origin of physical laws. Nor do we have any reason to assume that the powers of coordination are less fundamental than the physical laws. Neither the powers nor the laws are physical things, and what we can assume is that both come into play jointly, harmonizing with each other at the very origins of material manifestation. (We do not have matter first, and then the lawful ideas it obligingly “obeys.”) If anything, an inherent power to choreograph physically lawful activity in a meaningful manner, however poorly understood, would seem more fundamental — and more fundamentally generative or creative — than the physical lawfulness of the processes being choreographed.4

Given our ignorance of the ultimate nature of things, the most immediate path forward when the teleological question arises in a particular context, is simply to observe everything we can about the adjustment of means toward the fulfillment of needs and interests. In this way we get to know agency at work, just as we also get to know physical laws at work.

But this much can be said already. Wherever we find telos-realizing entities somehow bound together in a larger unity, we see one example after another where the more comprehensive entity or context manifests in turn a teleological character of its own that somehow “irradiates” and harmonizes the teleology of its parts. (Compare the whole organism and its relatively independent cells and organs.) Whether it is all the molecules in a cell, or all the cells in an organism, or all the organisms in a coherent group (say, an insect colony or mammalian social group), we always find a weaving of lower-level narratives into the distinctive and harmonious intentional fabric of a larger story.

So we can hardly help asking the teleological question in an evolutionary context: When a species consisting of many telos-directed individuals moves along a coherent evolutionary trajectory, do we see the species displaying its own sort of telos-directed developmental potentials? We must be willing to look with open and honest eyes.

“You speak of a harmonization of physical elements in tune with meaning and purpose. But how can this occur without relevant causal connections between the elements? We can see such connections clearly in a developing organism, where all the parts are contiguous. But huge numbers of different organisms in different, interacting species, often scattered over a large geographic area, are a different matter.”

Yes, a very different matter. And I know of nothing preventing us from hypothesizing that any purposive pattern of physical events requires that there be efficient causal connections between those events.

But this requirement for causal relations is hardly a problem, given that the members of evolving populations of organisms have no fewer or less relevant physical interactions than the aggregated cells in an individual body. Eating and being eaten are surely causal in the usual physical sense! And, of course, not only predator-prey relations, but also mating choices, territorial movements, various means of communication, lateral gene transfer mediated by microorganisms and viruses, and everything bearing on survival and death already figure importantly in conventional evolutionary theory.

Figure 18.2. Animals gathered at a dry watering hole in a Namibean national park.5

Isn’t the entire body of evolutionary theory today concerned with physical causation? Surely conventional theory is a physical theory, and its proponents believe they have all the causal interactions they need. The question about purpose, intention, and meaning is a question about the transformative organization and coordination of the physical processes already identified by evolutionary biologists. Or, to employ an older concept: it’s a question about the formal causes at work ordering all the efficient (physical) ones.

Actually, the reality of a coordinating power weaving through and governing large, scattered populations of organisms is already put on display for us before we even think about evolution. It is displayed, for example, in instinctual behavior such as that of migrating monarch butterflies in eastern North America. Huge numbers of these gather from throughout a wide area, including parts of the United States and Canada, and may travel thousands of miles over multiple generations to a precise spot in Mexico — all this along aerial pathways they have never traveled before. Later this well-directed journey is reversed.

Or consider the sophisticated collective behavior of a wolf pack, an ant colony, or even the cells — bacterial and otherwise — of a biofilm. The latter has been termed a “city for microbes,” and the complex, teleologically rich organization of a city is an apt picture of the life of a biofilm. In all these different sorts of collectives, the power of end-directed coordination, whatever we take it to be, seems to work across the relevant communities, all the way down to the molecules that actively participate in the bodily performance of the various organisms.

So I come back to my initial line of thought. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that an animal’s mating choices, its preparation of inheritances for its offspring, and all the other relevant causal factors are guided, or end-directed, in a manner leading to coherent evolutionary change. My point right now is not (yet) that this supposition is easily confirmed. I am only saying that it poses no further problems for our physical understanding beyond those already posed by all the cellular inheritances and other interactions within the many proliferating and radically diverging cell lineages in a complex, developing organism. These, too, are guided toward the future in a manner leading to coherent and progressive change.

And yet it all happens in what we might call a causally “closed” manner. There are no gaps in the succession of physically lawful interactions where we say, “Here a miracle occurs.” As I remarked above, the telos-direction of biological processes, like their physical lawfulness, appears to enter the picture at the very origins of material manifestation in organisms — not as an external imposition upon an essentially teleology-free material reality.

(Unfortunately, the “origin of material manifestation” is not a topic likely to come before the biologist’s attention. But see Chapter 24, “Is the Inanimate World an Interior Reality?”)

The relevant causal connections of an organism’s development do not suggest that the individual cell must consciously “know” about the developmental trajectory in which it is caught up. We can assume that the same would be true of an individual organism caught up in an evolutionary trajectory. In neither case would this “not knowing” prevent the individual entity from lending itself to, and being interpenetrated by, the larger end-directed process in which it participates. And it’s worth noting that neither the interpenetration nor the fact of a “larger process” is possible without an immaterial unifying idea, or formal cause, working across thing-like boundaries.

None of this is to deny that the particular principles of coordination in evolution must in some ways differ from those in individual development, as we will see shortly. But whatever the principles are, we will not discover them by looking at the laws of physics and chemistry. We will begin to grasp them only when we are able to read each particular context in terms of its own meanings, self-realizing powers, and directions of movement. We are already pretty good at this in the case of individual development. There is no reason not to try looking in an analogous way at evolving populations.

“It sounds as though your wonderful ‘agency’ can accomplish just about anything. But can you explain the presence or the nature of this agency?”

I pointed out above that we no more understand the nature and origin of the observed powers of meaningful, narrative coherence in living organisms than we do the nature and origin of physical laws in the inanimate realm. We don’t doubt the laws because we see them so clearly at work, and observing the patterns of their working has been enough for us. Perhaps this disciplined observation will also be enough when it comes to the powers of organic intention and purposiveness, once we overcome the taboo that says we can’t even look seriously at them.

We certainly know this much already: in every organism (that is, in all biology), diverse processes are coordinated toward a common end. This points toward a principle of interpenetration and unity (holism) that is universal in biology. The general rule is that we always find ourselves looking at wholes embedded within still larger wholes, and contexts overlapping other contexts. This is clearly evident when we consider the integrated unity of a physical body with all its cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems. It may take some effort, but we have to learn to think routinely in terms of this embeddedness of wholes and overlapping of contexts.

In Chapter 6 we heard how the botanist Agnes Arber described the relative character of organic wholes:

The biological explanation of a phenomenon is the discovery of its own intrinsic place in a nexus of relations, extending indefinitely in all directions. To explain it is to see it simultaneously in its full individuality (as a whole in itself), and in its subordinate position (as one element in a larger whole).

From flocks, herds, and schools, to bee and ant colonies, to parasitic and symbiotic pairs, to more or less closely aggregated communities of cells, to the collective, highly differentiated, and elaborately integrated communities of cells in our own bodies — there are many different contexts of agency. We discover agency and intention wherever we find participants bound together in a larger, more or less focal community that unfolds its purposive activity along a continuous and well-directed pathway according to its own distinctive meanings.

The honey bee hive functions, in this sense, as a (relative) whole with its own agency. We have no difficulty recognizing this agency in the hive’s pattern of coherently directed activity. The participants in the hive have no absolute discreteness or wholly independent identity. But neither do they lose all individual identity. It is a matter of one identity participating in a greater one.

If, as Arber suggests, biology presents us with interpenetrating wholes, then we should also expect to see interpenetrating agencies expressed in those wholes. The distinctive character of, say, a mammalian genus (or any other taxonomic group) is not silenced by, but rather informs, the character of each species within the group.

The question, “How does it all work?” calls only for closer observation of the detailed playing out of various general principles for which we already have ample evidence. (See, for example, Chapter 2, “The Organism’s Story.”) We may of course hope to come upon a deeper understanding of the nature and origin of biological agency. But I suspect that the demand for “something more” commonly stems from the errant feeling that if we can only identify more physical causes, they will spare us the need for formal causes and for the implied interiority.

“Isn’t the idea of agency, when applied to organisms in general, a rather disastrous anthropomorphism?”

Anthropomorphism is indeed a supreme danger in biology. Think, for example, of all the human activity we rather blindly import into the organism when we analogize it to a machine. (See the section about the machine model of organisms, in Chapter 10.) Similarly, it would be highly misleading to think of biological agency in general as if it were like the directive activity of an individual human agent.

To begin with, human agency itself is not as neat and unambiguous as we may be inclined to suppose. A fully sovereign individual does not exist. Who among us can say that he is motivated solely by his own will? Who does not at times yield gladly to internalized and inspiring “voices” — for example, of parents, teachers, and mentors, or religious figures, or uplifting literature? And who does not also wrestle with lower, less worthy urges? What young child subjected to extreme abuse does not carry into adulthood the burden and unfreedom of a psychic complex expressing some of the disastrous ideational, affective, and volitional powers of his abusers? Or again, which of us is absolutely immune to the collective ecstasy, hysteria, or rage of a massive crowd “rooting for the home team” or submitting to the spell of a charismatic leader?

It is true that, when we speak of agency, we speak of capacities we ourselves routinely and, at times, consciously exercise. But we must also admit that our experience of our own agency is closely bounded on all sides by mystery. We do not fully understand where our thoughts and actions come from, or how our intentions move our bodies. It would be a mistake to clothe the mystery of biological agency in the imagined form of a grandly sovereign, all-knowing, perfectly harmonious human individual.

And if we cannot be entirely clear about the sources of agency in our own lives, we can hardly be dogmatic about the nature of the agency — or diverse agencies — at work in a single bee colony, a particular species of rodent, or the biosphere as a whole.6

But nothing prevents us from being good observers of living beings, which is also to be observers of the clear manifestations of biological agency in its different forms. In this way we become familiar with the complex and perhaps many-voiced character — the way of being — of particular organisms. We learn to know “from the inside” one species as distinct from another, and from ourselves. See, for example, the description of the sloth in Chapter 12.

If we humans are part of nature and the evolutionary process, why should we think that anything in ourselves is absolutely alien to other organisms. It has been pointed out often enough that we carry something of the animal within ourselves. This seems to suggest that all animals carry something of the human within themselves. Recognizing sameness as well as difference, and difference as well as sameness, seems fundamental to the scientific project. If the anthropomorphic projection of human traits onto other organisms can be a problem, so can the denial of human traits as “unnatural.”

“But the simple fact is that evolution is not individual development. Don’t you need to reckon with this fact?”

Yes. One obvious difference between development and evolution is that cycles of individual development are endlessly and reliably repeated before our eyes, so that no one can avoid at least unconsciously recognizing their teleological character. Time and again, amid all the inconstancies of life and environment, mouse zygotes develop into adult mice, just as newborn dogs and cats become full-grown.

Evolution, by contrast, encompasses the totality of life on earth, and occurs only once. No more than in reading a good novel can we predict, mid-way through the story, its later outcome, even if that outcome turns out to be the end toward which everything was tending.7 This non-repeatability of evolution makes it all too easy, for those bent on doing so, to “forget” everything they know about the creative and end-directed character of all the life processes through which evolution occurs.

There are, of course, other distinctions between individual and evolutionary development. In the latter case we see (in those organisms reproducing sexually) a continual merging of separate hereditary lineages. There is also the fact of hybridization across species, genera, and even families. None of this occurs among the cells of a developing organism, even if cells have shown remarkable plasticity enabling, for example, the transformation of one cell type into another — up to and including the reversion of a differentiated cell into a stem cell — given the right contextual signals. And some evolutionary features figuring strongly in current theorizing — predator/prey relations, collective migrations, symbioses of various sorts, cultural inheritance, and lateral gene transfer — also serve to remind us that, while communities of organisms (think of the human microbiome) can be vitally important even for individual development, they become central in evolution.

We have no reason to assume that the play of purposiveness across all the cells of a complex, developing organism is exactly analogous to its play among the members of a species or population. Nor need we asume that the more or less fixed stages through which individual development passes give us a neat roadmap for the course of evolution.

We do, however, have at least one foundational principle: nothing can become a fact of bodily evolution that was not first a fact of individual development. The material substance of evolutionary transformation must first of all reveal itself within individual organisms. How these organisms subsequently merge (or fail to merge) their heritable features is another story.

The shortest path to

confusion is circular

One last question, or objection, deserves a section of its own. It could be put this way: Aren’t you committing an egregious sin of omission by ignoring what everyone knows? Natural selection explains everything that needs explaining about the appearance of agency and purposiveness. And it’s true, I’m sure, that any reader with a conventional biological training will share this concern. Natural selection, so the story goes, “naturalizes,” or explains away, the agency and purposiveness we observe in organisms. That is, explains it without appeal to any principles other than purely physical ones.

Biologists often think of purposiveness, or teleology, under the concept of function, as when they say that a trait is “for the sake of” this or that, or an organ exists “in order to” achieve a particular end. And so, as philosopher David Buller has summarized common usage, “the function of the heart is to pump blood, the function of the kidneys is to filter metabolic wastes from the blood, the function of the thymus is to manufacture lymphocytes, the function of cryptic coloration (as in chameleons) is to provide protection against predators.”

But all this poses difficulties for a science that would honor its materialist commitments, since the concept of function, as Buller observes, “does not appear to be wholly explicable in terms of ordinary causation familiar from the physical sciences.” Whereas kidneys may continually adjust their activities and their own structure in order to do the best possible job of filtering metabolic wastes from the blood, no physicist would say that falling objects adjust their activities and their own structure in order to reach, as best they can, the center of the earth. More generally, organisms may strive to live, but physical objects do not strive to maintain their own existence. Organisms, so it seems, have intentions of their own, whereas physical objects are simply moved from without according to universal law.

So the problem for biologists has been to explain, or explain away, their persistent and seemingly inescapable language of purpose, even if it is couched in terms of function. And the need is to do the explaining in a respectable, materialistic manner — that is, without acknowledging that organisms really are purposive beings in the sense of exercising, or being possessed by, an interior (immaterial) activity of a wise, meaning-infused and intentional sort. But this problem — so it might seem — has been fully solved in recent decades.

Buller, who was writing at the turn of the twenty-first century, was able to point to a “common core of agreement” representing “as great a consensus as has been achieved in philosophy” — an agreement that “the biological concept of function is to be analyzed in terms of the theory of evolution by natural selection.” More particularly, “there is consensus that the theory of evolution by natural selection can provide an analysis of the teleological concept of function strictly in terms of processes involving only efficient causation” — the kind of purposeless causation physical scientists accept as applicable to the inanimate world8 (Buller 1999).

So we no longer need to think of organisms as having genuine intentions, purposes, or telos-realizing drives issuing from their own interiors — no longer need to struggle with the problem of teleology, or end-directed activity. Teleology, we must believe, has been tamed, leaving biologists safe in a world without meanings, wisdom, purposiveness, intentions or other signs of living interiority.

To put the most common version of the idea very simply, organisms are said to possess teleological, or purposive, features because those features are present by virtue of natural selection. That is, they were selected for the very reason that they effectively serve the organism’s crucial ends of survival and reproduction. And since natural selection is supposed to be a perfectly natural process — meaning that it is supposed to involve nothing “mystical” like real purpose, intention, or thought — we can know that the functionally effective traits given us by natural selection are straightforward exemplars of physical lawfulness and nothing else, whatever they might look like.

The solution Buller alludes to amounts to saying: (1) purposive traits arise through natural selection; and (2) because natural selection is defined as a matter of genes, mutations, and patterns of life and death — all in a straightforward, mechanistic fashion — we can say that the organism’s evident purposiveness has been “naturalized.” Nothing of real purposiveness, as opposed to an apparent purposiveness, remains.

The assumption seems to be that one needs only to invoke natural selection in order to “naturalize” and explain any feature of life. In this manner one could say, for example, that natural selection explains faster-than-light teleportation simply because it is a useful trait conducing to survival. But if (hypothetically), upon seeing teleportation actually happening, we invoked natural selection to explain it, wouldn’t we still need to reconcile teleportation with our existing understanding of physical reality? By “solving” the problem with an appeal to natural selection, haven’t we simply shifted the burden of explanation from the biologist to the physicist — while also showing how natural selection can be said to solve a problem without actually solving it? (On unrealistic expectations for explanation by natural selection, see Chapter 16, “Let’s Not Begin With Natural Selection.”)

Buller does not even attempt to perform the work of the physicist here. He does not enlighten us in even the vaguest terms about how traits expressing the physically “impossible” aspects of purposiveness might have come about through natural selection. Which is to say that he does not solve the puzzle we saw posed in Chapter 8 (“The Mystery of an Unexpected Coherence”) regarding RNA splicing: How can we understand the intricate, complex, sequential operations of scores of molecules in a fluid milieu as they perform a kind of molecular surgery requiring a moment-by-moment exercise of intelligently directed intention allowing them to carry out this coherent surgery when they could just as well do a million other things? What they accomplish in a remarkably well-coordinated way is guided, not by gears, wires, levers, or incised channels of communication in silicon or any other material, but rather by the current and ever-changing needs, tasks, and functions of the local and more distant contexts.

What is happening with Buller here seems to me fairly obvious. He poses his initial problem in terms of reconciling a real interiority (purposiveness, intention, intelligence) with a materialistic conception of reality. But when he achieves his solution in terms of natural selection, he is no longer thinking of real interiority, but something more like a machine’s appearance of interiority, an appearance that comes about thanks to the design activity of a human engineer. So he has radically switched the terms of his problem, and feels no need (as long as he manages to ignore the human engineer) to explain how real interiority can be reconciled with his materialistic conception of the world. He’s just not dealing with the real problem of interiority any more.

The lacuna in conventional understanding here is truly astounding — or would seem so if biologists had not so routinely learned to hail natural selection as a kind of divine “Invisible Hand,” accounting for whatever needs accounting for.

As for natural selection more generally, there are three serious difficulties I will note here:

(1) The problem of the “arrival of the fittest” remains

To say that natural selection preserves traits promoting the survival of organisms does nothing to explain how those traits might have arisen, or even (as we have just seen) whether they are compatible with materialist thought. This depends on what the preserved traits are and how they arose. The preservation of an already existing trait is an entirely different matter from its nature and origin. In our present example, claiming that teleological features or activities already existed at some time in the past and then were preserved by natural selection merely pushes the problem of “naturalizing” them — making them acceptable solely in physical and materialist terms — back to an earlier time, without solving it.

We heard about this in Chapter 16, where prominent figures in evolutionary biology over the past century and more complained that natural selection — even if it explains the survival of the fittest — cannot explain the arrival of the fittest. In conventional evolutionary thought the arrival of traits is mostly taken for granted, with natural selection then playing a role in their preservation and their spread throughout a population.

Let’s put it this way. Yes, purposive features — if they could be had in a strictly physical world — would conduce to the survival of organisms, and therefore might be preserved. But the mere fact of preservation doesn’t show us that the features did in fact arise in a strictly physical world — doesn’t show us, in Buller’s words, that they are fully “explicable in terms of ordinary [physical] causation,” or are not expressions of a real, interior purposiveness.

Given the historical persistence of the complaint by leading biologists about natural selection and the arrival of the fittest, it is remarkable that the arguments today about how natural selection explains teleology generally proceed without so much as an acknowledgment of the problem.

(2) The explanation assumes what it is supposed to explain

It is important to realize that purposiveness is not just a particular, late-arriving trait, but runs through all biological activity. It is reflected in the coordinating principles that account for the integral, interwoven unity of the organism’s life. The complexity theorist and philosopher of biology, Peter Corning — who appears to hold a conventional, materialist view of life — was nevertheless gesturing toward this purposive unity when he wrote that living systems “must actively seek to survive and reproduce over time, and this existential problem requires that they must also be goal directed in an immediate, proximate sense … Every feature of a given organism can be viewed in terms of its relationship (for better or worse) to this fundamental, in-built, inescapable problem” (Corning 2019).

Rather than being just one more discrete trait that might have been neatly evolved at some particular point in evolution, the telos-realizing capacity of organisms reflects their fundamental nature. It is what “living” means. We are always looking at a live performance — a future-directed performance, improvised in the moment in the light of present conditions and ongoing needs — not a mere “rolling forward” of some blind physical mechanism.

Here we encounter a staggeringly obvious problem. You will recall from Chapter 16 that natural selection is supposed to occur when three conditions are met: there exists variation among organisms; particular variations are to a sufficient degree inherited by offspring; and there is a “struggle for survival” that tends to put the existing variants to a life-or-death test. But — and this is the crucial point — all the endlessly elaborate means for the production of variation, the assembly and transmission of inheritances, and the struggle for survival just are the well-regulated, end-directed activities whose teleological character biologists have tried to explain away. So the basic conditions enabling natural selection to occur could hardly be more thoroughly teleological.

In other words, the purposive performance of an organism is a pre-condition for anything that looks at all alive and capable of being caught up in evolutionary processes of trait selection. So the common form of the argument that natural selection explains the apparent purposiveness of all biological activity appears to assume the very thing it is supposed to explain. Purposiveness is built into the core presuppositions of natural selection itself, which therefore presents us with the problem instead of removing it. It would be truer to say that teleology explains natural selection than that selection explains teleology.9

Although this problem regarding the supposed explanation of teleology has been almost universally ignored among biologists, it has not been entirely overlooked. Georg Toepfer, a philosopher of biology at the Leibniz Center for Cultural Research in Berlin, has stated the matter with perfect directness:

With the acceptance of evolutionary theory, one popular strategy for accommodating teleological reasoning was to explain it by reference to selection in the past: functions were reconstructed as “selected effects.” But the theory of evolution obviously presupposes the existence of organisms as organized and regulated, i.e. functional systems. Therefore, evolutionary theory cannot provide the foundation for teleology10 (Toepfer 2012).

(3) There are no stable mechanisms for selection to work on

As was mentioned in Chapter 16 (“Let’s Not Begin With Natural Selection”), biologists conceive evolution by natural selection as tinkering with mechanisms that stably remain in place from generation to generation. These mechanisms can then be tinkered with further in the future. In this way, so it is thought, they can be improved, making it possible for complex and well-developed traits to be achieved over great spans of time.

The problem with this conception is that we never find the required sort of mechanisms in organisms, let alone stable mechanisms passed as such between generations so that they can be tinkered with over millions of years. This can perhaps be seen most clearly by looking at the molecular level, which virtually all contemporary biologists take as the ultimate basis for explanation.

Pick any substantive molecular process, such as RNA splicing (Chapter 8, “The Mystery of an Unexpected Coherence”) or DNA damage repair and you see hundreds of molecules cooperating in a task fully as complex as any brain surgery. It all happens while the molecular “surgeons,” lacking brains of their own, are moving in a watery medium with almost infinitely many physically possible interactions to “choose” from. There are no wires, gears, levers, or other mechanisms of control even remotely capable of simultaneously guiding the intricate, fluid interactions of all those interacting molecules and ensuring that the interactions occur, not haphazardly, but in exactly the right sequence — and no computer-like software able to coordinate and organize such mechanisms of control (Talbott 2024). We never see a command center issuing detailed instructions from which the interacting molecules might “read off” their moment-by-moment roles as each one of them collides with hundreds of thousands or millions of other molecules every second (Chapter 15, “Puzzles of the Microworld”).

The entire picture of the evolutionary tinkerer acting upon preserved mechanisms in a cumulative fashion through natural selection is a blatant fabrication. No mechanisms are there to be tinkered with, and none are even imaginable. There is not, and never was, anything like a mechanism to perform RNA splicing or DNA damage repair. Whatever is going on needs to be explained, not as the after-effect of a mechanism assembled at some time in the distant past, but as a wisdom intelligently at work in the present moment while taking full account of the changing and never fully predictable circumstances.

The same problem of the working of a present wisdom inheres in virtually every molecular process in every organism. Whether a cell is dividing or food is being digested, crucially important molecules are embarked upon an elaborate, reasonable, and meaningful journey the overall details and pattern of which are underwritten by no physical mechanisms. If there have been efforts to make the conventional picture of tinkerable mechanisms even marginally more realistic, I am not aware of them.

![]()

What, then, can we make of the theory of natural selection? It’s a theory misleadingly focused on the idea of individual fitness rather than on the evolutionary outcome that is the final object of explanation — an outcome that could involve a crucial role for distinctly “unfit” organisms; a theory that has not even managed to define its pivotal parameter — the single organism’s fitness — with any scientific clarity; a supposedly causal, evolutionary theory quite unable to understand the genesis of the “ubiquitous variation” in traits it takes for granted; a theory that, when it does allude to these traits, says no more than that they somehow correlate with randomly generated mutations, where the appeal to randomness not only is the very opposite of scientific explanation, but also seems to contradict the infinitely complex, wholly intentional, thoroughly qualitative, interwoven unity of being of a shark or kangaroo or a dog or cat; and a theory founded aggressively and restrictively on the genome — that is, on a single aspect of the cell rather than on the whole-cell life that so obviously governs the genome.

It appears, then, that there’s not much compelling about the contemporary theory of evolution by natural selection. Without a clear definition of the problem it is meant to solve, it has veered off into various scientific research strategies that certainly have led to many profitable observations of organisms and their interactions, and certainly have produced a great deal of data about changes in relatively minor traits — changes that are often reversed later, as in the famous case of the coloring of peppered moths in England — all in the absence of anything we could call a fundamental theory of evolution. Perhaps it is no wonder that so many who would speak for science on the topic of evolution today, as we saw in Chapter 16, prefer to celebrate the “inevitable” logic of natural selection instead of demonstrating its explanatory contribution to our understanding of actual evolutionary transformations.

An aversion

to meaning

The theory of natural selection gives us no argument explaining away the self-evident purposiveness of organisms. To the contrary, it confirms the theorist’s largely unacknowledged recognition of this purposiveness. For we can make sense of natural selection only after we have thoroughly internalized, from childhood on, a vivid awareness of the lively agency, whether of cats and dogs, birds and squirrels, worms and fish, or of the animals in our laboratories. The scientist can take this agency for granted without having to mention or describe it, since everyone else also takes it for granted. It’s what we observe every day.

This may be an extraordinarily naïve way to do science and philosophy, but, well, there it is. And so one speaks ever so casually of individual “development,” or the “struggle for life,” or the “production of variation,” or “reproduction and inheritance” — all in order silently to import into theory the full range of the living powers that made biology a distinct science in the first place, but that few today are willing to acknowledge explicitly in their theorizing.

Several decades ago the British biologists Gerry Webster and Brian Goodwin had already noticed that “the organism as a real entity, existing in its own right, has virtually no place in contemporary biological theory” (Webster and Goodwin 1982). Goodwin later elaborated the point in his book, How the Leopard Changed Its Spots:

A striking paradox that has emerged from Darwin’s way of approaching biological questions is that organisms, which he took to be primary examples of living nature, have faded away to the point where they no longer exist as fundamental and irreducible units of life. Organisms have been replaced by genes and their products as the basic elements of biological reality (Goodwin 1994, p. vii).

The banishing of organisms from evolutionary theory was also an obscuring of biological purposiveness. It may even be that the banishing happened mainly for the sake of this obscuring. Yet who can doubt that, if we ever do take the purposive organism into account at anything like face value, the results could be of explosive significance for all of evolutionary theory?

It is difficult to pinpoint whatever lies behind the extraordinary animus the biological community as a whole holds, not only toward teleology, but indeed toward any meaningful dimension of life or the world. But the animus seems as deeply rooted as it could possibly be. Michael Ruse, who might be regarded as a dean of contemporary philosophers of biology, once briefly referred to an article by the highly respected chemist and philosopher, Michael Polanyi, in this manner:

Polanyi speaks approvingly, almost lovingly, of “an integrative power … which guides the growth of embryonic fragments to form the morphological features to which they embryologically belong.”

And what was Ruse’s response?

One suspects, indeed fears, that for all their sweet reasonableness the Polanyis of this world are cryptovitalists at heart, with the consequent deep antipathy to seeing organisms as being as essentially physico-chemical as anything else … Shades of entelechies here! (Ruse 1979)

Figure 18.3. Michael Polanyi. Having made many scientific contributions, Polanyi became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was a Gifford lecturer, and author of the books, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy and The Tacit Dimension, among others.11

The assumption that the Polanyis of this world are antipathetic toward the idea that organisms are “as essentially physico-chemical as anything else” is a mere distraction from the real issue. No one needs to, or should, deny that organisms are perfectly reliable and unexceptionable in their physical and chemical nature. (Certainly Polanyi did not deny this.) By injecting his unfounded “suspicions” into his argument, Ruse simply abandons his responsibility as a philosopher to deal honestly with his antagonist’s thought.

The real question has to do with the distinctive organizing ideas we find to be characteristic of organisms. After all, no one claims that the lawful ideas of the physicist are mystical just because laws are not physical things. They belong to the immaterial nature of inanimate phenomena. So why should we refuse to acknowledge the readily observable organizing ideas characteristic of animate phenomena? There is a burden of explanation here that Ruse seems not even to recognize, let alone to engage.

The real antipathy appears to be on Ruse’s part. One wonders exactly what violation of observable truth he saw in Polanyi’s reference to “an integrative power” that “guides” embryological growth. No biologist would dare deny that embryological development is somehow integrated and guided toward a mature state. And it is difficult to understand how any actual integrating and guiding could be less than the expression of an effective “power,” however we might end up understanding that term. Just think how much less justification there is for all the conventional references to the “power,” “force,” and “guidance” of natural selection! (On that, see Chapter 16, “Let’s Not Begin With Natural Selection.”)

As for Ruse’s shuddering at the term “entelechy” (sometimes rendered as “soul”), the scholar who is perhaps the foremost interpreter of Aristotle today translates the Greek entelecheia as “being-at-work-staying-itself” (Sachs 1995, p. 245). What better characterization of an organism and its distinctiveness relative to inanimate objects could there possibly be? Every biologist who uses the conventional term “homeostasis” (a system’s maintenance of its own material stability) or, better, “homeorhesis” (a system’s maintenance of its characteristic activity) is already saying something similar to “being-at-work-staying-itself.” It’s the way of being of any organism. The Aristotelian term is useful for reminding us that an organism is first of all an activity, and its activity is that of a centered agency possessing a remarkable coordinating and integrative power in the service of its own life and interests.

On our part, we will now do our best to begin reading the organism and its activity back into evolutionary theory. In doing so, we will ignore the strange taboo against acknowledging living powers and purposiveness wherever we see them at work.

Is Teleology Disallowed in the Theory of Evolution?

An animal’s development from zygote to maturity is a classic picture of telos-realizing activity. Through its agency and purposiveness, an animal holds its disparate parts in an effective unity, making a single, ever more fully realized whole of them. This purposiveness extends “downward” from the whole so as to inform the parts, and “outward” from the inner (immaterial) intention toward the exterior (material and perceivable) expression. It is invisible to any strictly physical analysis of the interaction of one part with another.

Biologists in general have failed to take seriously the reality of the organism’s agency, and have considered it unthinkable that something analogous to the agency playing through all the cells of an individual organism could play through all the members of an evolving population of organisms. The main lesson of this chapter is that we have no obvious grounds for making a radical distinction between the two cases.

A central point is that we no more understand the origin and nature of physical laws than we understand the origin and nature of biological agency. Nevertheless, we are quite able in both cases to observe how they work.

Moreover, the current unwillingness of biologists to reckon with the possibility that evolution gives us a coherent, telos-realizing narrative does not appear to be explained by the differences between individual development and evolution (which are very real), but rather by a refusal to take seriously the problem of active biological wisdom and agency in either case.

The uncomfortable truth is that biologists have yet to come to terms with the physically puzzling fact of purposive biological activity — which is to say, all biological activity. To suggest that evolution is telos-realizing is not to suggest some new kind of problem. It is merely to say: let’s face up to the reality of teleological development and behavior that has already long been staring us in the face.

We also looked at three closely related problems with the general consensus among biologists that natural selection somehow explains (or explains away) biological agency and purposiveness:

• The preservation of purposive (functional) traits — or any traits at all — by natural selection neither explains their origin nor shows how they can be understood solely in terms of physical lawfulness.

• Selection itself is defined in terms of, and thoroughly depends on, the purposive lives of organisms. This purposiveness must come to intense expression in order to provide the basic pre-conditions for natural selection. These conditions are the production of variation; the assembly and transmission of an inheritance; and the struggle for survival. Since the entire logic of natural selection is rooted in a play of purposiveness, it cannot explain that purposiveness.

• Biologists conceive natural selection as tinkering with mechanisms that survive as such from generation to generation, so that they can be tinkered with further in order to achieve complex and well-developed traits. The problem with this conception is that there are no such enduring mechanisms to be progressively tinkered with. It is impossible to think of scores or hundreds of molecules cooperating in a watery medium to achieve an intricate task such as RNA splicing or DNA damage repair as if they constituted fixed, stable mechanisms that natural selection could tinker with over evolutionary time spans.

My aim in this chapter has been to clear away some of the major stumbling blocks biologists inevitably conjure up whenever they hear it said that evolution has a purposive, or teleological, character. Of course, there remains the question whether evolution does in fact show such a character. Does the evolution of species show the same kind of thought-imbued creativity we see at work in the development of individual organisms? Or, perhaps: can we intelligently imagine such an organic wisdom not being at work?

We will see that — just as with individual development — the question is answered as soon as it is asked. Once the metaphysical biases against the very idea of teleology are removed, all we need to do is look, and it’s as if our eyes themselves are enough to give us our answer.

Notes

1. Rich, Watson and Wyllie 1999. The authors go on to mention that, while researchers naturally tend to focus on cell survivors, “it is striking that, even with a sophisticated understanding of survival signals, we still know remarkably little of the reciprocal process by which, of the seven million germ cells present in the ovary of the mid-term human foetus, the vast majority is lost by the time of birth.”

2. Green 2022:

Every second, something on the order of one million cells die in our bodies. This is a good thing, because cell death is central to efficient homeostasis and adaptation to a changing environment. When, for some reason, it does not occur, the consequences can be catastrophic, manifesting as cancer, autoimmunity, or other maladies.

3. Figure credit: Courtesy of Dr. Christoph Grüter, leader of the Insect Behaviour and Ecology research group at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom.

4. This choreography of physical processes occurring at the root of material manifestation is very different from the human engineer’s arrangement of a machine’s parts “from the outside.” I discuss the machine model of organisms in Chapter 10 (“What Is the Problem of Form?”).

5. Figure 18.2 credit: mejaguar (https://www.pickpik.com/africa-namibia-nature-dry-national-park-water-hole-11349), public domain.

6. Owen Barfield once wrote a kind of didactic fantasy novel (Barfield 1965, p. 163) in which the protagonist had conversations with a higher being modeled after the “maggid” of Jewish mystical tradition. The final words of that being — and of the novel — depict an “interwoveness” of a hierarchy of living and guiding agencies that may perhaps be suggestive in the present context:

Twice, answered the gentle but inexorable voice, twice now you have called me “Master.” But what you shall do shall be taught you not by me, neither by my masters. You may only receive it direct from the Master of my masters; who is also their humble servant, as each one of them also is mine; as you — if your “doing” should be only a writing — will strive to be your reader’s, and asI am

yours.

7. Actually, the same unpredictability is true of individual development. If we were watching a developmental sequence for the first time, we would not be able to predict its mature outcome based on what we saw during the early phases. And yet we might recognize retrospectively that this outcome was the end toward which everything was tending all along.

8. Here is a more complete statement from Buller:

Consider how natural selection provides an explanation of why humans, for example, have hearts. The heart is a complex organ and all complex traits are the product of accumulated modifications to antecedently existing structures. These modifications to existing structures occur randomly as a result of genetic mutation or recombination. When they occur, there is variation in a population of organisms (if there wasn’t already) with respect to some trait. If one of the variants of the trait provides its possessor(s) with an advantage in the competition for survival and reproduction, then that variant will become better represented in the population in subsequent generations. When this occurs, that variant of the trait has increased the relative fitness of its possessor(s) and there has been “selection for” that variant. That variant can then provide the basis for further modification. Thus, humans have hearts because hearts were the product of randomly generated modifications to preexisting structures that were preserved or maintained by natural selection due to their providing their possessors with a competitive edge. So natural selection explains the presence of a trait by explaining how it was preserved after being randomly generated.

9. From Georg Toepfer (see also the immediately following citation of Toepfer in the main text):

Most biological objects do not even exist as definite entities apart from the teleological perspective. This is because biological systems are not given as definite amounts of matter or structures with a certain form. They instead persist as functionally integrated entities while their matter and form changes. The period of existence of an organism is not determined by the conservation of its matter or form, but by the preservation of the cycle of its activities … Biologists can identify in every organism devices for protection, feeding, reproduction or parental care irrespective of their material realization. These functional categories play the most crucial role in biological analyses (Toepfer 2012).

10. There is also this from University of Toronto philosopher of biology, Denis Walsh. Natural selection, he says, occurs

because individuals are capable of mounting adaptive responses to perturbations. This capacity to adapt allows individuals to survive in unpredictable environments and to reproduce with startling fidelity, despite the presence of mutations. It is adaptation which explains the distinctive features of natural selection in the organic realm and not the other way round. (Walsh 2000).

Therefore, he adds, “the programme of reductive teleology cannot be successfully carried out.” Then there is the following succinctly stated criticism by the independent philosopher, James Barham:

Selection theory does nothing to help us understand what it is about functions that makes it appropriate to speak [in a physically unsupported way] of their “advantage,” “benefit,” “utility,” etc. for their bearers. Natural selection is like a conveyor belt which transmits a biological trait or function from one generation to the next … But natural selection cannot explain how the capacity of biological functions for success or failure arose out of physics in the first place, for the simple reason that the selection process has no hand in constituting biological traits as functions (Barham 2000).

And, finally, in 1962 the philosopher Grace de Laguna wrote a paper in which she remarked that only when we regard the organism as already “end-directed” does it “make sense to speak of ‘selection’ at all” (de Laguna 1962).

Given my limited familiarity with the literature, I would not be surprised if there exist a few similar criticisms along the same line, at least among philosophers. But my own experience suggests that finding them amid all the conventional evolutionary thinking requires some serious digging.

11. Figure 18.3 credit: Store Norske Leksikon (https://snl.no/Michael_Polanyi), public domain.

Sources

Arber, Agnes (1985). The Mind and the Eye: A Study of the Biologist’s Standpoint, with an introduction by P. R. Bell. Originally published in 1954. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Barfield, Owen (1965). Unancestral Voice. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Barfield, Owen (1971). What Coleridge Thought. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Barham, James (2000). Biofunctional Realism and the Problem of Teleology, Evolution and Cognition vol. 6, no. 1.

Buller, David J. (1999). Natural Teleology, introduction to Function, Selection, and Design, edited by David J. Buller. Albany NY: SUNY Press, pp. 1-27.

Corning, Peter A. (2019). Teleonomy and the Proximate–Ultimate Distinction Revisited, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 127, no. 4 (August), pp. 912-16. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blz087

Goodwin, Brian (1994). How the Leopard Changed Its Spots: The Evolution of Complexity. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Green, Douglas R. (2022). A Matter of Life and Death, Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology vol. 14, no. 1 (January 4). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a041004

de Laguna, Grace A. (1962). The Role of Teleonomy in Evolution, Philosophy of Science vol. 29, no. 2 (April), pp. 117-31. doi:10.1086/287855

Rich, Tina, Christine J. Watson and Andrew Wyllie (1999). Apoptosis: The Germs of Death, Nature Cell Biology vol. 1 (July), pp. E69-71. doi:10.1038/11038

Ruse, Michael (1979). Philosophy of Biology Today: No Grounds for Complacency, Philosophia vol. 8, (October), pp. 785–96. doi:10.1007/BF02379065

Sachs, Joe (1995). Aristotle’s Physics: A Guided Study. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Talbott, Stephen (2024). How Do Biomolecules ‘Know’ What To Do? https://bwo.life/bk/ps/biomolecules.htm

Toepfer, Georg (2012). Teleology and Its Constitutive Role for Biology as the Science of Organized Systems in Nature, Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences vol. 43, pp. 113-19. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2011.05.010

Walsh, Denis (2000). Chasing Shadows: Natural Selection and Adaptation, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part C: Biological and Biomedical Sciences vol. 31, no. 1 (March), pp. 135-53. doi:10.1016/S1369-8486(99)00041-2

Webster, Gerry and Brian C. Goodwin (1982). The Origin of Species: A Structuralist Approach, Journal of Social and Biological Structures vol. 5, pp. 15-47. doi:10.1016/S0140-1750(82)91390-2

This document: https://bwo.life/bk/evotelos.htm

Steve Talbott :: Teleology and Evolution: Why Can’t We Have ‘Evolution on Purpose’?