Biology Worthy of Life

An experiment in revivifying biology

Vladimir Solovyov on Sexual Love and Evolution

Stephen L. TalbottPostings on this site ostensibly relate to the current biological literature. However, it happens that older writings are sometimes, and in some respects, more “current” than current ones. I intend to stir things up now and then by bringing forward one of these neglected sources of intellectual stimulation.

For an earlier example of this in a different venue, see When Holism Was the Future, dealing with the early twentieth-century marine biologist, E. S. Russell. His critique of chromosome theory remains as relevant and profound as most anything you can read today. We have also made available some extended extracts from one of Russell’s books under the title, From Mechanistic to Organismal Biology.

![]()

I offer here a straightforward summary of parts of Solovyov’s argument, allowing it to stand on its own despite the limitations of nineteenth-century biological knowledge and despite expressions that are bound to grate on modern ears. Yes, the ideas presented here reflect Solovyov’s peculiar era and culture and may therefore appear oddly provincial and dated. But this can usefully remind us that our own thought-forms are, in at least some respects, equally provincial and dated — and will be experienced as such by others soon enough. Far better if we don’t leave that experience entirely to them. Sometimes the easiest way out of the unconsciously constraining assumptions of one’s own cultural context is to listen as earnestly and sympathetically as possible to the “alien” testimony of an earlier era or foreign culture.

These words by Owen Barfield in the book’s preface may serve as an Abstract:

[Solovyov] opens with a biological survey which easily, and to my mind irresistibly, refutes the age-old assumption … that the teleology of sexual attraction is the preservation of the species by multiplication. On the contrary, it is apparent from the whole tendency of biological evolution that nature’s purpose or goal (or whatever continuity it is that the concept of evolution presupposes) has been the development of more complex and, with that, of more highly individualized and thus more perfect organisms. From the fish to the higher mammals quantity of offspring steadily decreases as subtlety of organic structure increases; reproduction is in inverse proportion to specific quality. On the other hand, the factor of sexual attraction in bringing about reproduction is in direct proportion. On the next or sociological level he has little difficulty in showing that the same is true of the factor of romantic passion in sexual attraction. Both history and literature show that it contributes nothing towards the production of either more or better offspring, and may often, as in the case of Romeo and Juliet, actually frustrate any such production at all.

Why then has nature, or the evolutionary process, taken the trouble to bring about this obtrusively conspicuous ingredient in the make-up of homo sapiens? …

Being, at the level of human individuality, is characterized above all by a relation between whole and part that is different from the everyday one that is familiar to us. We may catch a glimpse of it if we reflect, in some depth, on the true nature of a great work of art. … It is a relation no longer limited by the manacles of space and time, so that interpenetration replaces aggregation; one where the part becomes more specifically and individually a part — and thus [to that extent] an end in itself — precisely as it comes more and more to contain and represent the Whole.

Sex-love is for most human beings their first, if not their only, concrete experience of the possibility of such an interpenetration with other parts, and thus potentially with the Whole.

But first a brief biographical note1:

An Urge to Reconcile Opposites

On January 26, 1878, two days before his twenty-fifth birthday, Vladimir Solovyov stood up before an audience of intellectuals and officials in St. Petersburg to begin the first of his twelve Lectures on Divine Humanity. The lectures aimed at concretely demonstrating the reality of the evolution of human consciousness and religion. Among the attendees was Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who, although much older than Solovyov, was already a close friend. Also attending was Leo Tolstoy, with whom Solovyov would carry on a much more “antagonistic” relationship2.

The precocious Solovyov became widely known through these early lectures and his even earlier publications. During his teenage years, he had been “possessed by a passionate and violent atheism” (Jakim 1995). Having entered Moscow University at age sixteen under the sway of positivism and utilitarianism, he pursued three years of study in physics and mathematics before switching to the Faculty of History and Philology. “As a mark of both his talent and his audacity, he received his degree in June of 1873 without completing any classes as an official student of that faculty”. A year and a half later he defended his master’s thesis. Thereafter he took up theological studies, and then he would return to the Faculty of History and Philology for his doctorate.

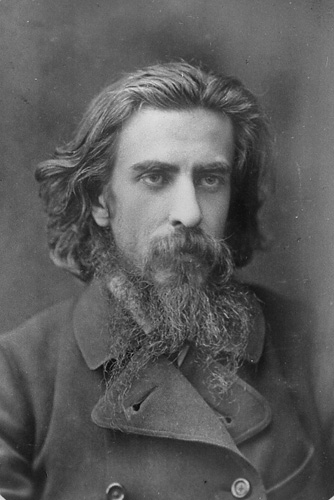

Vladimir Solovyov

The impressive body of work Solovyov completed during his twenties included these major publications: The Crisis of Western Philosophy: Against Positivism (parts of which were published before submission as his master’s thesis); The Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge, concerned with the nature of organic rather than abstractly logical knowledge; A Critique of Abstract Principles (doctoral thesis); and Lectures on Divine Humanity. He was, during that third decade of his life, already considered an important figure on the Russian intellectual scene, and he would eventually be regarded by many as the most significant and influential Russian philosopher of the nineteenth century.

Solovyov, however, could not remain comfortable living the life of an academic, and in fact spent much of his life as a wanderer of sorts. He died “surrounded by friends but with neither a family nor a home of his own”. Yet despite what almost appeared to be vagrancy at times, his academic credentials remained secure throughout his life. During his last decade “he was asked to be the philosophy editor of the important multivolume Encyclopaedic Dictionary … [he] wrote dozens of articles for the encyclopedia on ancient and modern philosophers and on such philosophical topics as beauty, reason, nature, mysticism, and evil”.

But there were other sides of his life, which I can scarcely attempt to capture. He claimed to have had three visitations from, or visions of — a figure he identified as “Sophia”, or “Divine Wisdom”, and he spent a lifetime trying to come to terms with these experiences. This led him into what are usually referred to as “mystical” pursuits. Yet his drive to hold the different aspects of his life together — he also achieved considerable work as a poet, literary critic, political commentator, and theologian — was always solidly grounded. He had little tolerance for detachment from the material world, whether in the form of abstract religiosity and mysticism, or abstract science. In all matters he sought an understanding that could lead to transformation and elevation of the world, not an escape from it.

It is also noteworthy that he often ridiculed himself, whether in verse or otherwise. “Some of his poetry makes fun of his own most precious beliefs”, and his self-mockery extended even to, or especially to, his bumbling search for the truth of Sophia. “Solovyov seems to have wanted his audience to laugh at his quest for Divine Wisdom”.

More generally, he was known for his irreverent epigrams, pranks, and sometimes crude jokes, showing a “willingness to mix earthly humor and divine love, as well as laughter and metaphysics”. Embracing opposites in the hope of raising them to a higher unity, he was “a vegetarian in a land of meat-filled pastries and cutlets, a Slavophile who rejected Russian nationalism, and a scholar willing to give up a stable university career to speak out against the tsar”. This may help explain the perplexingly diverse views of his life and work:

Despite his popularity, Solovyov consistently provoked criticism from Russians of all schools. For Slavophiles, he focused too much on the West; for Westernizers and liberals, he was an irrational mystic; for Orthodox clergy, he was a freethinker who flirted with Catholicism; for Tolstoyans, he supported Orthodox doctrine; for Dostoevsky’s reactionary acolytes, he was too sympathetic to Jews. In an article on the Slavophiles written in 1889, Solovyov ironically points to the number of conflicting labels attached to him by the press: Catholic, Protestant, rationalist, mystic, nihilist, Old Believer, and, finally, Jew.

Readers of the following may be particularly interested to know that Solovyov never married. He acknowledged “serial infatuations” as a young person, and carried on a number of idealized relationships with women as an adult, at least one of them (with a married woman) lasting some twenty-three years to the end of his life. That particular woman happened to be named “Sophia”, and she was among those at his bedside as he died.

The Testimony of Natural History

While Solovyov does not speak like a twenty-first century biologist, his argument is thoroughly rooted in natural and evolutionary history. To begin with: the truth that “propagation of living creatures may take place without sexual love is already clear from the fact that it does take place without division into sexes”. And since the sexual factor is not connected with propagation in general but only with the propagation of higher organisms, we must seek the meaning of sexual differentiation and sexual love, not in the idea of the species and its propagation, “but only in the idea of the higher organism”.

Broadly reviewing the vertebrates, Solovyov notes the production of offspring on a tremendous scale (up to millions annually) among fishes, where fertilization takes place outside the body of the female, and where “the method by which this is done does not admit of the supposition of any powerful sexual impulse”.

Amphibians and reptiles are far less prolific than fish, but they engage in more intimate sexual relations. Birds, are still less prolific, “yet the sexual attraction and the mutual attachment between male and female attain a development unheard of in the two lower classes”. Among mammals — where the young are at first borne within the mother’s body — the power of propagation is in general even weaker than among birds; the sexual attraction, on the other hand, while often less constant than among the birds, is far more intense. And in humans, while propagation occurs on the smallest scale, “sexual love attains its utmost significance and its highest power, uniting in the superlative degree, both constancy in the relation (as in birds) and intensity of passion (as in mammals)”.

Solovyov on “Sexual Love”

The term “sexual love”, for Solovyov, did not refer (as it likely would today) specifically to a physical act, but more generally to the love between a man and a woman:“I call sexual love, for want of a better term, the exclusive attachment (one-sided as well as mutual) between persons of different sexes which makes possible the relation between them of husband and wife, but in no wise do I prejudge by this the question of the importance of the physical side of the matter.”

“Love is important not as one of our feelings, but as the transfer of all our interest in life from ourselves to another, as the shifting of the very center of our personal lives. This is characteristic of every kind of love, but predominantly of sexual love; it is distinguished from other kinds of love by greater intensity, by a more engrossing character, and by the possibility of more complete overall reciprocity.”

So, then, at one extreme we find massive propagation without sexual love, and, at the other, intense sexual love with minimal propagation, or none at all. It is clear, then, writes Solovyov, that sexual love and propagation “cannot be bonded indissolubly with one another”. Each possesses its own independent significance. Among humans sexual love “assumes that individual character by power of which just this person of the other sex possesses for the lover absolute significance, as unique and irreplaceable, as a very end in itself”.

If love were nature’s way of securing more or better offspring, it would be odd, Solovyov remarks, that unusually powerful love often remains unrequited or, if mutually shared, leads to tragedy — and, even without the tragedy, commonly remains unfruitful.

In general, “a powerful, individualized love never exists as an instrument of service for the ends of the species, which are attained apart from it”. As for human history, sexual love “plays no role in and shows no direct influence upon, the historical process: its positive significance must have its roots in individual life”.

Significance of the Self-Aware Human Individual

Among animals, the life of the species takes precedence over the individual, whose efforts tend primarily to benefit the species. In this context, sexual attraction, manifested in sexual rivalry and figuring in natural selection, serves not merely for reproduction of organisms, but also for the generation of more perfect organisms.

In humans, by contrast, individuality achieves a significance that changes everything. The expression of the human personality is never made a passive and transient instrument of an evolutionary process external to it. This judgment, far from expressing mere human conceit, follows from the rational consciousness attained in human beings. Quite apart from sentience and whatever consciousness he shares with animals, the human individual can evaluate his own states and actions in their relation to “universal ideal norms”.

The point here is central for Solovyov. The individual human mind is “not merely the organ of personal life, but likewise the organ of remembrance and divination for the whole of humanity, and even for the whole of nature”. Capable of a rational understanding of truth and of conforming his actions to this higher consciousness, “the human may infinitely perfect his life and nature, without departing from the limits of human form”. This leads Solovyov to the conviction, not that evolution stops with humans, but that its continuation remains thoroughly human:

What rational basis can be conceived for the creation of new things, in essence more perfect forms, when there is already a form capable of infinite self-perfection, able to make room for all the fullness of absolute content? With the appearance of such a form further progress can consist only in new degrees of its own development, and not in its replacement by any creations whatsoever of another kind.

Here, where Solovyov’s thought may appear quite foreign to modern ideas, it also connects with current notions about how the possibilities for evolution change in the light of human culture — and also with the idea, occasionally voiced, that the human individual is more or less analogous to the animal species. Another way to get at the latter point would be to say that, for humanity, the problem of the origin of species becomes the problem of individual transformation.

Among less individuated organisms, the situation is altogether different. According to Solovyov, “the succession of higher forms from lower ones … is a fact absolutely external and alien to the animals themselves, a fact quite nonexistent for them”. The elephant and ape know nothing about the evolutionary conditions of their own existence. Even the progressively higher development of a particular or isolated organism’s consciousness does not contribute to the enlargement of the general consciousness, “which is as absolutely absent in these intelligent animals as in a stupid oyster”.

The importance of being conscious. (An editorial comment:) Consciousness, of course — especially when raised to the power of reason — is problematic for the material-minded biologist, who in many contexts prefers to ignore it. But this is to put out of view the profoundest of biological facts: consciousness alone is where the evolutionary process is first fully and explicitly realized. Evolution here “comes into its own” and declares itself in human awareness. That which has gone on from the beginning now operates, at least in part, through the conscious choice of the individual and the quest for universal ideals.

In slightly different words: what must be realized through individual human striving today can be seen as an expression — a further development and transformation — of the very processes that were at work in simpler, less individuated life forms. When we observe animals of increasing complexity, we notice a progressive internalization of function and an expansion of interior, sentient life, culminating in self-awareness. That which worked on the organism throughout evolutionary history to develop this capacity for self-awareness, now works through the human being in the exercise of this capacity. Is there any reason to doubt that it is the same power in both cases?

All of which suggests that evolution has had a certain mindful character all along — or a more-than-mindful character, inasmuch as the power to engender minds can hardly be alien or inferior to the capacity of the minds it engenders.

That, I hope, is a fair gloss upon Solovyov’s remarks about consciousness. It would be well to realize, in any case, that we are in no position to reject his emphasis on the central role of consciousness in evolution before we have at least half-begun our own reckoning with the still largely ignored relation between consciousness and evolutionary biology (Nagel 2012*).

Individual, Society, Cosmos

The importance of the individual, for Solovyov, is bound up with the “positive unity of all”, since through the human being there can shine forth the truth of the entire universe. The individual thereby becomes “the center of the universal consciousness of nature”.

This “positive unity of all”, along with the “universal consciousness of nature”, is perhaps where Solovyov’s thought becomes most difficult. In his larger body of work he seems always to be approaching these notions — and always from different directions. He is, in general, acutely aware of the fragmentation of human experience and of the world constituted by this experience. And he is preoccupied with the potentials to overcome this fragmentation and achieve wholeness.

Beyond mutual impenetrability. In The Meaning of Love Solovyov speaks of a two-fold impenetrability of things: they are separated from each other both in time and in space. “That which lies at the basis of our world is being in a state of disintegration, being dismembered into parts and moments which exclude one another”.

Overcoming this disintegration — re-membering ourselves and the world in which we live — is, as Solovyov sees it, a personal and social task with cosmic implications. Moreover, it is a task consistent with what we can already recognize, behind the disintegration, as the essential “unity of all”.

He cites — to give but one example of the principle of unity — a simple, profound, and universal physical phenomenon, one that would change a great deal of modern thought if we would only spend some time contemplating it: I mean the phenomenon of two objects gravitationally attracting each other. In Solovyov’s language: here we see that “parts of the material world do not exclude one another, but, on the contrary, aspire mutually to include one another and to mingle with each other”.

We could not retain our commonplace image of separate parts if we truly reckoned with the mutual participation of two objects gravitationally attracted to each other. It is not a matter of one object exerting an external force upon another “from a distance” (as students are often asked to imagine the matter), but of two entities caught up in a single, unified embrace wherein the being — the very substance and activity — of one is inseparable from that of the other. This truth, evident enough to the physicist, suggests that there is something pathological about our routine habits of perception through which we form our picture of a world consisting of separate and disconnected objects.

All our universe, insofar as it is not a chaos of discrete atoms but a single and united whole, presupposes, over and above its fragmentary material, a form of unity, and likewise an active power subduing to this unity elements antagonistic to it. … The body of the universe is the totality of the real-ideal, the psycho-physical ... Matter in itself, i.e., the dead conglomeration of inert and impenetrable atoms, is only conceived by abstracting intelligence, but is not observed or revealed in any such actuality.

That is a remarkable statement, coming as it did before the early twentieth-century revolution in physics. Solovyov points out that there can be no such thing as a “material unity” — not, at least, as matter is normally conceived. “Material things” just coexist side by side. Any unity must be ideal. After all, even the mathematical laws of physics, which offer one route toward a unified understanding of phenomena, are ideas — but ideas that belong both to our understanding and to the nature of things themselves.

Solovyov goes on to speak about the relation between the single animal and the species, the human individual and society, and the potential of the latter relation to become an image of, and contribute to, a universal or cosmic unity. Of course, this juxtaposition of human society and the cosmos, of earthly evolution and cosmic evolution, is one of those places where the twentieth-century biologist is likely to recoil in learned horror.

While these aspects of Solovyov’s thought are beyond the scope of this article, we would do well to recall a primary reason for the horrified recoil: namely, the Cartesian split of the world into two incommensurable substances — thinking substance and extended substance. Once we see beyond this supposed incommensurability, can we really believe the cosmos to be barricaded against the evolution of human consciousness3?

For anyone who should wish to pursue such matters, I can do no better than recommend Owen Barfield’s Poetic Diction (1973*) and Saving the Appearances (1965*), ideally to be read in that order.

Sexual love as the redemption of individuality. The human capacity to recognize and realize truth “is not only generic but also individual: each human is capable of recognizing and realizing truth, each may become a living reflection of the absolutely whole, a conscious and independent organ of the universal life”. In the rest of nature there is also truth, “but only in its objective communality, unknown to the particular creatures. It forms them and acts in them and through them — as a fateful power, as the very law of their being, unknown to them, to which they are subject involuntarily and unconsciously. … Here love appears as a one-sided triumph of the general, the generic, over the individual”.

Solovyov expands on this difference between humans and animals by noting that egoism is the source of individual life and of the idea of the Whole. But egoism is not enough either for a true individual or for the genuine unity of the Whole, for through it a man affirms his particular being “as a whole for itself, wishing to be all in separation from the all — outside the truth”. On the other hand,

Truth as a living power that takes possession of the internal being of a human and actually rescues him from false self-assertion is termed Love. Love as the actual abrogation of egoism is the real justification and salvation of individuality.

Varieties of Love

Biologists must come to terms with other forms of love as well. Solovyov considers these, but finds each of them, whatever its profound virtues, unable to play the full evolutionary role of sexual love:Patriotism and love of humanity cannot do away with egoism because there is such a great incommensurability between the lover and the loved. “Humanity, and even the nation, cannot be for the individual being the selfsame concrete object as he is himself”.

In maternal love “there cannot be full reciprocity and living interchange, for the very reason that the lover and the loved ones belong to different generations, that for the latter life is in the future with new independent interests and tasks, in the midst of which representatives of the past appear only like pale shadows. … The mother whose whole soul is wrapped up in her children does of course sacrifice her egoism, but at the same time she loses her individuality … For the mother, though her child is dearer than all, yet it is only just as her child ...”

“Friendship between persons of one and the same sex is lacking in the overall difference in form, in qualities which complete each other”.

The object of mystical love “comes in the long run to an absolute indistinction, which swallows up the human individuality. Here egoism is abrogated only in that very insufficient sense in which it is abrogated when a person falls into a state of very deep sleep (to which it is compared in the Upanishads and the Vedas, where at times also the union of individual souls is directly identified with the universal spirit). Between a living human and the mystical ‘Abyss’ of absolute indistinction, owing to the complete heterogeneity and incommensurability of these magnitudes, not only living interchange, but even simple compatibility cannot exist”.

In sum: human love signifies “the justification and salvation of individuality through the sacrifice of egoism”. The problem with egoism is not that we value ourselves too highly. Indeed, to deny absolute worth to ourselves would be to deny human worth altogether. No, the problem is that the significance we ascribe to ourselves is denied to others.

Of course, nearly everyone, in an abstract, theoretical sense, grants the principle of equality to others. But with any self-awareness at all, it is easy enough for us to recognize (painful as the recognition may be) that in our “innermost feelings and deeds” we assume “complete incommensurability” between ourselves and others. I am everything, they are nothing. And so far as I hold this attitude, I can hardly claim absolute worth even for myself. Such worth is more a potential than a reality. “I” can become “all” only together with others.

“True individuality is a certain specific likeness of the unity-of-the-all, a certain specific means of receiving and appropriating to oneself all that is other”. In reality, egoism impoverishes the individual by cutting him off from greater meaning. The one power that can undermine egoism is “love, and chiefly sexual love”. It compels us, “not by abstract consciousness, but by an internal emotion and the will of life to recognize for ourselves the absolute significance of another”. We realize our own truth and significance precisely “in our capacity to live not only in ourselves, but also in another”.

A note of caution. It would be easy, but very mistaken, to take Solovyov as belittling other forms of love. If sexual love (as he defines it; see Box 1 above) offers a particularly great potential, it is because it can include within itself other sorts of love that, in whatever degree, shift the center of attention from oneself to another — everything from instinctual affection and human friendship to eros and agape (“unconditional” or “self-sacrificing” or “divine” love). But this is just to say that all these participate in the meaning of love in Solovyov’s sense. “For good reason”, he writes, the relations between members of different sexes

are not merely termed love, but are also generally acknowledged to represent love par excellence, being the type and ideal of all other kinds of love.

Moreover, the elevated language so natural to this context is inseparable from the most down-to-earth issues of organismal health — and therefore cannot be irrelevant to evolution. Amitai Etzioni, director of George Washington University’s Institute for Communitarian Policy Studies, was recently asked for a clarification of the meaning of “communitarian”, and he replied:

We must continue to move away from pure self-interest and toward the common good. Communitarianism refers to investing time and energy in relations with the other, including family, friends and members of one’s community. The term also encompasses service to the common good, such as volunteering, national service, and politics. Communitarian life is not centered around altruism but around mutuality, in the sense that deeper and thicker involvement with the other is rewarding to both the recipient and the giver. Indeed, numerous studies show that communitarian pursuits breed deep contentment. A study of 50-year-old men shows that those with friendships are far less likely to experience heart disease. Another shows that life satisfaction in older adults is higher for those who participate in community service. (Etzioni 2014*)

I am sure Solovyov would recognize in this a strong affirmation of the “meaning of love” — this despite the fact that Etzioni is not discussing the man-woman relations that (potentially) encompass everything he is talking about and much more.

Love: An Unrealized Reality

Solovyov is a realist. When we look around ourselves — or at ourselves — we see that “love is a dream, which temporarily possesses our being and then disappears without ever carrying over into actuality”. But the fact that an ideal is unrealized does not mean it is unrealizable. To think otherwise is to lose sight of the human capacity for self-development. After all, the arts and sciences, the modern forms of civic community, our powers over nature — even rational consciousness itself — were once unrealized potentials.

Love is as yet for humans what reason was for the animal world: it exists in its beginnings, or as an earnest of what it will be, but not as yet in actual fact. … The task of love consists in justifying in deed that meaning of love which at first is given only in feeling. It demands such a union of two given finite natures as would create out of them one absolute ideal personality.

(Keep in mind that “one absolute ideal personality” never connotes for Solovyov the submergence or disappearance of the individuals involved. He is speaking precisely about the achievement of individuality. His is a picture of organic unity, and therefore requires ever more individualized participants in direct proportion to the intensity and expressive power of the unity they achieve. By comparison, think how, as animals grow more complex, the heart and lungs become more perfect as organs in their own right; and, at the same time, they become more essential to, and more elaborately integrated into, the organism as a whole. This helps us to understand how, in certain lower organisms such as flatworms or salamanders, major parts of the body, when amputated, proceed to regrow, whereas in higher animals this doesn’t happen. In the lower organism the unity is simpler and less differentiated, allowing what remains to regenerate the missing part. In higher organisms the differentiation of ever more sophisticated and individuated parts demands an intensification of the interweaving and unifying processes, which in turn makes for greater indivisibility of the whole. The part becomes less separable from the whole just insofar as it gains a more perfect identity of its own.)

Love, like speech, is a fact of nature, not something humans arbitrarily thought up. It is not a mere illusion; it is there as an objective reality. And, also like speech, it is something we can enter into and develop further. It would have been a sad thing, says Solovyov, if humans had left speech undeveloped, so that we spoke only as birds sing rather than making language an instrument for our own ever-new and ever-higher ends. “Such significance as the word possesses for the formation of human society and culture, love also possesses in a still greater degree for the creation of true human individuality”.

Solovyov continues this comparison:

The highest task of true language is already foreordained by the very nature of words, which inevitably represent general and permanent ideas, not separate and transient impressions … They bring us to the comprehension of universal meaning. In a similar fashion the highest task of love is already marked out beforehand in the very feeling of love itself, which inevitably and prior to any kind of realization introduces its object into the sphere of absolute individuality, sees it in ideal light, and has faith in its absoluteness. Thus in both cases (in the realm of verbal cognition and likewise in the realm of love), the task consists not in thinking up anything whatsoever completely new out of one’s own mind, but only in consistently carrying farther and right to the end what has already been given in germ.

And yet, he adds, whereas the use of language has developed tremendously, we seem largely at a standstill regarding love, having gained only a few, poorly understood rudiments of its reality.

Nevertheless, for a moment at least, the lover sees in the beloved what others do not. And even if this “light of love” quickly dims, we need not conclude that the initial vision was false. It may have been a temporary and unaccustomed insight into the true being of the beloved. No one would deny that the world beheld by humans in general is richer and fuller than that beheld by a mole. So, likewise, some humans live within a world vastly richer and fuller of truth than others can see. The lover may have perceived what the rest of us cannot.

For Solovyov, the true being of the beloved, as of every person, is an image of God. And so, from its first flashing forth, love signals “the visible restoration of the Divine image in the material world, the beginning of the embodiment of true ideal humanity. The power of love, passing into the world, transforming and spiritualizing the form of external phenomena, reveals to us its objective might, and after that it is up to us. We ourselves must understand this revelation and take advantage of it, so that it may not remain a passing and enigmatic flash of some mystery”.

Concluding Note

Sadly, I must end my survey here, leaving it incomplete, since with mention of “the Divine image” (if not also with many previously cited remarks!) the author passes beyond anything likely to be tolerated by the majority of contemporary biologists. Yet there are grounds for questioning this intolerance. If we leave aside any religious implications of the word “Divine”, there remains something to say about the general notion of an image being realized in the evolutionary process or in humanity.

The many words overlapping in meaning with image include not only species, but also nature, type (or archetype), form, and essence. While type and essence in particular have long been in disrepute, we have lately been hearing suggestions that these terms were unjustly vilified during the reductionist heydays of the “neo-Darwinian” Modern Synthesis and molecular biology. (See, for example, Riegner 2013*; Walsh 2006*; and Winsor 2006*.) The problem has been a gross misconstrual of type (and related terms) owing to the nearly immovable reductionist and materialist biases of our time.

Someday (so I dream) biologists will step back and see evolution with new eyes. By this I mean they will recognize that they see with ideas as well as with sense organs, and that if they see truly, the ideas belong as much to the things seen as to the one who sees. Moreover, they will understand that the archetypal ideas manifesting in nature are both dynamic (forever “becoming other in order to remain themselves” — Brady 1987*) and potent (causally capable of guiding their own dynamic expression in appropriate contexts).

But these are not matters I can take up here. My immediate aim in this concluding note, rather, is to put the reader on notice that we will shortly be making available on the Nature Institute website the just-cited (but out-of-print) book chapter by the late philosopher, Ronald Brady. Dealing centrally with problems of form and type, Brady contends in his luminous essay that we discover in biology forms that are causal. Further, he provides the means for every reader to make the discovery for herself. If Evo-Devo (evolutionary developmental biology) ever finds its proper footing, I suspect this 1987 paper will come to be regarded as a foundational forerunner of the field.

More to the present point: Brady’s paper makes perfect background reading for Solovyov’s reference to an immaterial image being realized in human development and evolution.

Notes

1. I draw mainly from the biographical sketch by Judith Kornblatt (2009*). Quotes are from that work unless otherwise indicated.

2. However, “the two collaborated on a letter concerning the defense of the Jews, published in England by Solovyov and undersigned by Tolstoy, among other leading intellectuals”.

3. We are poorly positioned to identify what is wrong with a foreign way of thinking until we deeply understand the basis for that thinking — until we can sense for ourselves how it once could have felt so natural and compelling. And the particular way of thinking we are talking about here — whereby the human “microcosm” intimately participated in the great macrocosm — was almost universally felt to be natural until just a few hundred years ago.

Sources:

Barfield, Owen (1965). Saving the Appearances. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World. Originally published in 1957.

Barfield, Owen (1973). Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press. Originally published in 1928.

Barfield, Owen (1977). “Form in Art and in Society”, in The Rediscovery of Meaning, and Other Essays, pp. 217-27. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Brady, Ronald H. (1987; reprint forthcoming). “Form and Cause in Goethe’s Morphology”, in Goethe and the Sciences: A Reappraisal, edited by F. Amrine, F. J. Zucker, and H. Wheeler, pp. 257-300. Expected to be available by August 31, 2014 at https://natureinstitute.org/txt/rb/index.htm

Etzioni, Amitai (2014). “Communitarian Observations”, email newsletter of the Institute for Communitarian Policy Studies, (July 30).

Jakim, Boris (1995). “Editor’s Introduction” to Lectures on Divine Humanity by Vladimir Solovyov, pp. vii-xvi. Hudson NY: Lindisfarne.

Kornblatt, Judith Deutsch (2009). Divine Sophia: The Wisdom Writings of Vladimir Solovyov. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press.

Nagel, Thomas (2012a). Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature Is Almost Certainly False. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Riegner, Mark F. (2013a). “Ancestor of the New Archetypal Biology: Goethe’s Dynamic Typology as a Model for Contemporary Evolutionary Developmental Biology”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences vol. 44, no. 4, Part B (Dec.), pp. 735-44. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2013.05.019. (To request a copy of Riegner’s article, write him at mriegner@prescott.edu.)

Solovyov, Vladimir (1985). The Meaning of Love, edited with a substantially revised translation by Thomas R. Beyer, Jr.; introduction by Owen Barfield. Hudson NY: Lindisfarne Press.

Walsh, Denis (2006). “Evolutionary Essentialism”, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science vol. 57, pp. 425-48. doi:10.1093/bjps/axl001

Winsor, Mary P. (2006). “The Creation of the Essentialism Story: An Exercise in Metahistory”, History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences vol. 28, pp. 149-74.

Further information:

On the essential relation between part and whole, explored in terms of the human individual and society, see Owen Barfield’s essay, “Form in Art and in Society” (cited in references above).

This document: https://bwo.life/org/comm/ar/2014/love_22.htm

Steve Talbott :: Vladimir Solovyov on Sexual Love and Evolution